Why China Has No Inflation

By Peng Kuang-hsi

This is a pamphlet published by the Foreign Languages Press in Peking (Beijing) in 1976, during the Mao era. The complete text of the pamphlet is given here, although the collection of photographs of people at market places, etc., which was included in the original pamphlet, is omitted here. —Scott H.

Contents

An Introduction

1. PEOPLE ARE FREE FROM INFLATION WORRIES

Stable Price Level; Improving Livelihood

Savings Banks Instead of Pawnshops

Renminbi’s Prestige Grows in the World

2. HOW THE CONSEQUENCES OF THE INFLATION WERE ELIMINATED

Worst Inflation in World History

A Long-Cherished Dream Comes True

3. WHAT IS THE “SECRET” OF RENMINBI’S LONG-TERM STABILITY?

The Socialist System Is the Safeguard

The Key: A Growing Socialist Economy

The Circulation of Money Is Planned

Unified Price Management

Steadfast Policy of Fiscal Balance

Balance of Credit

Differential Pricing for Domestic and Foreign Markets

An Introduction

ALL OVER the world, the capitalist economy is in turmoil. Ordinary people and their families are haunted daily by inflation. How to get rid of the menace has become a most widely discussed problem in many parts of the world. In sharp contrast is the situation in the People’s Republic of China. In the quarter of a century since its founding, thanks to the continuous growth of China’s socialist economy based on the policy of independence and self-reliance, and to the full display of mass initiative, the people’s livelihood has steadily improved. A remarkable feature in this respect is the stability of Renminbi [RMB] (People’s Currency)—the Chinese yuan.

How did China overcome the aftermath of the runaway inflation that prevailed on the eve of the liberation? Why is her currency immune from the monetary crises that have wrecked the capitalist world in all these years? How does the stability of RMB affect the daily life of her people? Answers are given in this booklet, based on a survey by the writer who had visited a number of families, checked with markets and interviewed government departments in charge of finance, banking and commerce.

These facts are presented in the hope that they may help the foreign reader to a better understanding of New China’s financial and monetary systems, her economic policy and the life of her people.

1

People Are Free from Inflation Worries

MONEY IS an indispensable medium in daily life. Through it we obtain food, clothing and so on. This is true of every country in our era of monetary economies. Therefore, ups and downs in the value of money are of concern to everyone. Yet people I spoke to during this survey gave little thought to possible changes in the value of RMB. Many housewives don’t even know what “inflation” means.

Why? At the Statistical Bureau of the Peking Municipality, a table attracted my attention.

| Purchasing Power of RMB in Peking (1965 = 100) | ||||

| |

1966 | 1968 | 1970 | 1973 |

| For goods | 100.22 | 100.52 | 101.32 | 101.57 |

| For services | 102.23 | 102.52 | 102.52 | 103.20 |

These figures tell us that 100 yuan at their 1965 value could buy 101.57 yuan worth of goods in 1973; and in services (rent, water, electricity, bus fare, etc.) they could buy 103.20 yuan worth. Thus, the value of the yuan is not only stable, but shows a slight upward trend.

The Peking scene is representative of the whole country. China’s yuan remains stable today despite the inflation raging in the entire capitalist world.

Stable Price Level; Improving Livelihood

The level of prices is an important indicator of a nation’s economy. It reflects the purchasing power of money, and serves as a yardstick of the people’s livelihood. Below is a worker’s family budget in China.

The Chang Family’s Budget

“You see, food, clothing and other necessities have cost the same all these years,” the 36-year-old textile worker Chang Pao-chih said to me when we talked of what he spends. “My family doesn’t have a high standard of living, but our income covers our needs and we don’t worry that our money will buy less.” His words clearly demonstrate the stability of prices in China, which in turn contributes to a secure life for her people.

Chang is a production team leader in a workshop of the Peking No. 2 State Textile Mill. His wife Chang Shu-hua, also 36, tends a cone-winding machine there. Their combined monthly income is 154 yuan. They have two children, one in primary school, the other in a day-nursery. The Changs breakfast and dine at home and lunch in the factory’s dining hall, which is located near their home. They are a rather typical family in China.

For an understanding of the impact of price level on the life of the people, I tabulated the family budget of the Changs.

| Family Budget — Monthly Average (In yuan) | |||

| Item | 1965 | 1970 | 1974 |

| Grain | 23.60 | 25.45 | 25.45 |

| Meat, vegetables, etc. | 22.50 | 30.00 | 30.00 |

| Dining out | 12.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 |

| Sugar, fruit and refreshments | 10.00 | 10.00 | 9.50 |

| Clothing | 16.75 | 21.35 | 21.35 |

| Rent | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| Water | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Electricity | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.05 |

| Gas | 1.60 | 1.60 | 1.60 |

| Bus fare, stamps | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| Recreation | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 |

| Haircuts, baths | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Day-nursery | 3.50 | 3.50 | 3.50 |

| Contingent outlays | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

Total |

99.80 |

113.75 |

113.25 |

Apart from spending on food and clothing, which increased in these ten years due to the birth and growth of the children, all other amounts have remained the same. So the family is able to put aside more than 40 yuan a month in the bank. With this money, the Changs have bought a radio, a TV set, two wrist watches and some furniture. Their home is adequately furnished.

On Sundays, they all have their meals at home, and the groceries cost about 2 yuan. What do they get for this money? According to Peking retail prices from 1965 to November 1974, 2 yuan could buy the following:

In 1965,

Pork 0.25 kilogramme Eggs 0.25 " Ribbon fish 1.00 " Bean curd 0.50 " Cabbages 0.50 "

In 1974,

Pork 0.25 kilogramme Eggs 0.25 " Ribbon fish 1.00 " Bean curd 0.50 " Cabbages 0.50 " Potatoes 0.50 " Green onions 0.50 "

That is to say, their food basket was a little heavier in 1974 for the same amount of money, reflecting the stability of prices.

Groceries Cost the Same

In Peking’s grocery stores and markets, price lists painted on boards in red, blue or white ink years ago are still unchanged. At the counters one may often hear a child sent to shop calling out:

“A kilogramme of salt, please.”

“Half kilo of soybean sauce, please.”

The child is used to the price, puts down the required cash, and goes off with the purchases without worrying about any error.

Most Peking grocery store prices have remained the same for years. And some have gone down a bit. This is shown by a survey for November, 1974, as compared with 1970 and 1965.

| Retail Prices, Peking (Per kilogramme, in Yuan) | |||

| Item | 1965 | 1970 | 1974 |

| Pork | 2.00 | 1.80 | 1.80 |

| Mutton | 1.42 | 1.42 | 1.42 |

| Beef | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 |

| Dressed chicken | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Ribbon fish | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Eggs | 2.08 | 1.80 | 1.80 |

| Bean curd | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| Cabages | 0.058 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Potatoes | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.20 |

| Green onions | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.18 |

Peking is amply supplied with vegetables at all seasons. The big markets at Tungtan, Hsitan, and Chaoyangmen carry more than 100 varieties for most of the year, and over 50 even in winter. Residents hailing from the south can find vegetables once peculiar to their regions but now grown in people’s communes in Peking’s outskirts, as are some foreign species including the sunset hibiscus of Africa, the lettuce of Europe and America, the coffee senna of Southeast Asia and a type of rape indigenous to Japan.

Average daily per capita consumption of fresh vegetables in Peking is 0.5 kilogramme, or double the level of the period immediately following the liberation. Seasonal adjustments are made in vegetable prices, but the average, in the past ten years, has stayed around 0.08 yuan per kilogramme. Staples like tomato and Chinese cabbage, when in season, are piled in huge heaps along the streets, and sold at 0.10 yuan per 2-3 kilogrammes.

All types of bean products in cakes, sheets, shreds, pulp and many other forms, much favoured by Peking’s consumers, sell at prices unchanged since 1956.

Prices of Other Daily Necessities Stable, a Few Marked Down

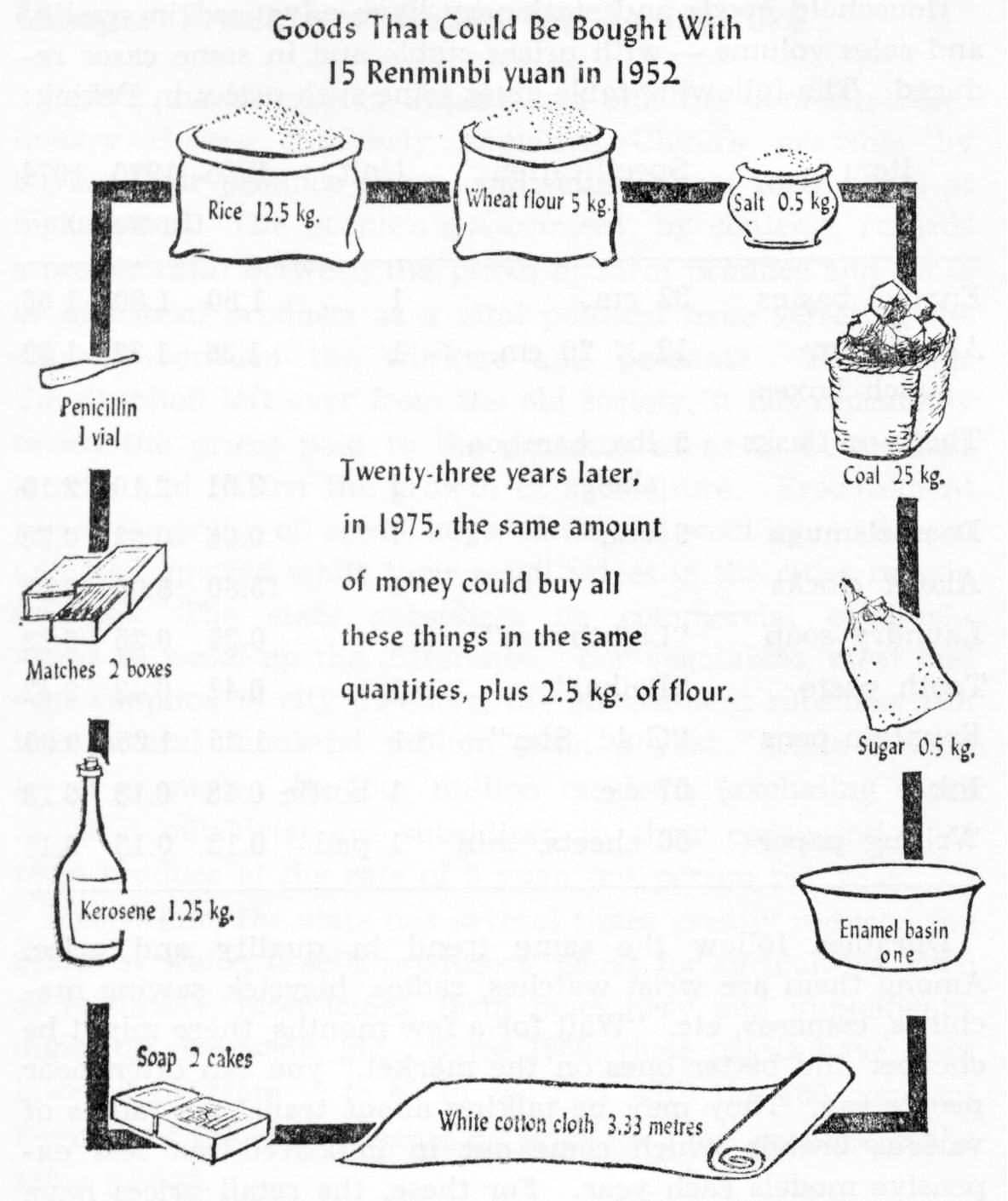

As we have seen from the Chang family budget, prices of grain and fuel in 1974 were still the same as in 1965. Moreover, they have been stable since the years immediately following liberation. For a sampling of goods that could be bought with 15 yuan in 1952 in Peking’s markets, see the diagram [immediately below].

Now, 23 years later, for the same amount of money one can obtain all these things in the same quantities, plus 2.5 kilogrammes of flour.

The system of state purchasing and marketing of grain was set up in 1953. Since then, to increase the income of the peasants, the state has several times raised its purchase prices for grain, while keeping its retail prices in the towns at approximately the same level. China’s consumers are also immune from the present upward trend of grain prices on the world market. The average retail prices for grain staples in China today are, for example: wheat flour (medium grade), 0.36 yuan per kilogramme; and rice, 0.286 yuan per kilogramme. They are virtually the same as the state’s purchase price paid to the producers. All costs of storage and transportation and the losses in the course of handling by commercial departments are covered by a state subsidy which amounts to about 2.5 million yuan for every 50 million kilogrammes (50,000 metric tons) of grain.

For clothing, cotton materials are available in increasing variety, and sales of woollen, silk, and synthetic piece goods have increased quickly. Staple items such as drills, cotton gabardines, and calico (printed and plain white) have not varied in price. For instance, the price of 1chih (1/3 metre) of plain white calico in Peking, Tientsin and Shanghai, has for yers been 0.28 yuan—equivalent to that of a pack of common cigarettes.

Household goods and stationery have advanced in quality and sales volume—with prices stable and in some cases reduced. The following table gives some such prices in Peking:

| Item | Specification | Unit | 1965 | 1970 | 1974 |

| (In yuan) | |||||

| Enamel basis | 32 cm. | 1 | 1.80 | 1.80 | 1.66 |

| Aluminium lunch boxes |

12 x 20 cm. | 1 | 1.36 | 1.32 | 1.32 |

| Thermos flasks | 5 lbs, bamboo shell |

1 | 2.51 | 2.10 | 2.10 |

| Enamel mugs | 9 cm. | 1 | 0.96 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| Alarm clocks | |

1 | 15.80 | 8.00 | 8.00 |

| Laundry soap | “Lighthouse” | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.22 |

| Tooth paste | “Beihai” | 1 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.42 |

| Fountain pens | “Gold Star” | 1 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 0.90 |

| Ink | 57 c.c. | 1 bottle | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| Writing paper | 50 sheets, thin | 1 pad | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

Durables follow the same trend in quality and price. Among them are wrist watches, radios, bicycles, sewing machines, cameras, etc. “Wait for a few months, there might be cheaper and better ones on the market,” you can often hear people say. They may be talking about transistor radios of various brands which come out in improved but less expensive models each year. For these, the retail prices have been cut by an average of 40 per cent from 1965 to 1974. Most drastic are the price cuts for medicines. Today, in China, their cost is only one-fifth that in 1950, the year after liberation. For what used to be 50 cents worth of medicine then, one pays only 10 cents today.

Cheaper Producers’ Goods for Agriculture

Before the liberation, imperialism and the domestic reactionary classes ruthlessly exploited China’s peasants by buying their produce cheap, and selling them their needs at high prices. The people’s government, by contrast, regards a proper ratio between the prices of farm produce and those of industrial products as a vital political issue affecting the alliance between the workers and peasants. To change the situation left over from the old society, it has repeatedly raised the prices paid to the peasants so as to boost their income and hasten the growth of agriculture. Procurement prices for grain, oil seeds, hogs, cattle and wool have all been adjusted upward while their retail prices in the cities remain constant. The state subsidizes its commercial establishments to make up the difference. For vegetables, meat and eggs supplied to city dwellers, the government subsidies run into several thousand million yuan a year. Take Peking as an example. Its four million residents (excluding those in rural outskirts) are subsidized in their consumption of farm produce at the rate of 5 yuan per person per year.

Meanwhile, the state has several times greatly reduced the prices at which it sells producers’ goods for agriculture, such as fertilizers, insecticides, farm machinery and implements, diesel oil, kerosene, etc. Since 1950, their prices have been lowered by from 1/3 to 2/3, in contrast with the 100 per cent increase of the state purchasing price for farm produce in the same period.

These measures have narrowed down the disparity by 45 per cent. That is, a given amount of farm produce can now be exchanged for move industrial products. Below is a table illustrating this trend. The figures are for Abganar (Silinhot) in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

| Rural Produce |

Equivalent in industrial goods |

Year | |||

| 1950 | 1965 | 1972 | 1974 | ||

| A draught horse |

Plain white cloth (in metres) |

84 | 480 | 505 | 514 |

| A bullock | Flour (in kg.) |

165 | 195 | 253 | 253 |

| A sheep | Tea brick (pieces) |

1.9 | 4.0 | 4.6 | 4.6 |

| Wool (50 kg.) | Sugar (in kg.) |

31.7 | 50.5 | 71 | 77 |

Regional and seasonal differences in price used to be a means by which the reactionary ruling classes and speculators exploited the working people, exacting excessive profit by purchasing at dirt-cheap prices and selling at sky-high ones. Since the liberation, the state commercial departments have narrowed down regional price differences step by step, and eliminated irrational seasonal price changes for major farm produce, especially in the distant border and minority nationality regions. Prices for fertilizers, insecticides, medicines, etc. are uniform throughout the country—a thing inconceivable in old China.

Cheap Rents and Utilities

The rent paid by the Changs is 0.84 yuan per month. They told me it has not changed for fifteen years, ever since they moved in.

Their two-room apartment, with 24 square metres of floor space, has central heating, gas and the use of a kitchen and toilet. In the bigger room, the main furnishings are a double bed, chest of drawers, wardrobe, and desk, and it serves also as a living room. As the apartment building was erected by their factory for its employees, the rent is practically free. It is less than one per cent of the Changs’ combined income, so they are very satisfied.

A more usual rent is that charged for government-built flats which are let directly to tenants. At the Yuehtan residential area in the western section of Peking, I visited a family of four (a neighbourhood factory worker, her husband, and two daughters still in school) who live in a two-room apartment in a government housing project. The unit with 33 square metres of floor space has a kitchen, toilet and two built-in closets. The family pays a monthly rent of 5.6 yuan, 4.6 per cent of their income. The flat is centrally heated, equipped with gas facilities and adorned by a balcony.

Why are rents so low? Residents who recall suffering from exorbitant rents before the liberation stress the superiority of the socialist system as the explanation. For additional detail and further understanding, I interviewed Comrade Ti Tsung of the Peking Housing Bureau. He said the total housing available to Peking residents at the time of the liberation amounted to some 13 million square metres. Since then, more than 22 million square metres have been built. Thus, more and more people are living in new buildings, and the rents are low.

In government-owned old-style houses, the rent averages 0.20 yuan per square metre; in apartment houses of several storeys it is slightly under 0.30 yuan. As already stated, government agencies and factories charge even less for the living quarters occupied by their employees. All in all, for a family of five living in a two-room, 30-square-metre apartment in Peking, the rent is about 5 yuan for a month, or 3-5 per cent of average combined income of husband and wife.

Like rents, the charges for utilities have remained low. For water they fell by 33.3 per cent in the period 1965-74 and now stand at 0.12 yuan per ton (1,016 litres). Household electricity has all along been billed at 0.148 yuan per kilowatt-hour.

With the growth of China’s oil industry, a great number of Peking households have shifted to the use of gas for cooking. The price for bottled gas (15 kilogrammes per bottle) went down by 25 per cent from 1965 to 1974.

Fares on city buses and trolley and on the railways have remained the same for years. Airline fares have been drastically reduced to a figure roughly the same as those for Class-A sleepers, thus attracting many more people to air travel.

Unchanged Service Charges

In the Chang’s family budget, the outlay for recreation, haircuts and baths has remained almost the same for years, and represents a small fraction of the total. Apart from unvarying charges at the cinemas, theatres, barbershops and bathhouses, workers and employees enjoy many fringe benefits in these respects.

A ticket for a first-run film in Peking costs at most 0.30 yuan, and for other films from 0.25 yuan to a minimum of 0.10 yuan. All school children—primary and intermediate—pay 0.05 yuan for any film, feature or documentary. Theatre admission costs 0.30-0.50 yuan. Factories, enterprises or government agencies sometimes issued free tickets to their workers and staff. Admission to larger parks is 0.05 yuan; to the Palace Museum and the Museum of Revolutionary History, it is 0.10 yuan. That has been so ever since the liberation.

Many organizations provide free barbershops and bathhouses for their employees, while family members pay half the outside rate. All factories and enterprises issue free coupons for such services as part of their collective welfare provisions. Townspeople without these benefits pay a maximum of 0.40 yuan (for men) or 0.50 yuan (for women) at the barbershop, and from 0.15 to 0.26 yuan for a bath. These rates, too, have not changed since the liberation.

Medical expenses in the Chang’s family budget are low. This is because the adults, as workers, enjoy complete free health service, while the two children get it at half price. They are seldom ill, and when they are, medicines are very cheap.

Lastly, the cost of schooling and nursery service. For their elder child, in primary school, the Changs pay 2.50 yuan per school term (half a year). This covers miscellaneous expenses, tuition itself being free in all schools up to the college level. Colleges do not charge any miscellaneous fees, and house their students free. Thus in China, the financial burden borne by parents for their children’s education is very light. The younger Chang child goes to the factory’s day-care centre, which charges 3.50 yuan per month. In Peking as a whole, all-week nurseries charge 9.00 yuan, or at most 10.00 yuan per child per month. These rates, too, have stayed the same for years, which is another sidelight on the stability of the RMB.

Savings Banks Instead of Pawnshops

We visited the local office of a bank on Hufangchiao Street outside of Chienmen, an old city gate of Peking. It is in a small, simple building. On the door is a shingle, “Hufangchiao District Office, People’s Bank of China, Hsuanwu Area, Peking.” Though a district office, it ranks with a branch bank and is not a small unit. Yet there is no hint here of the ostentatious railings or tall buildings that used to demonstrate the power of money in pre-liberation banks. One walks directly into a room with rows of long tables, where the business is done. Throughout working hours, ordinary people come and go in large numbers.

“In recent years, more and more people—workers, government employees, teachers, housewives, students and so on—have put money in our bank,” said Comrade Li Yueh-hsin in charge of the savings department. “The stability of the yuan draws an ever wider range of people to bank their savings for long periods, giving support to socialist construction.” In 1974 alone, 5,600 new accounts were opened in this district office, and the total savings deposits there have increased by 40 per cent comparing with 1965. Of these accounts, 80 per cent are time deposits.

In China’s old society, working people had nothing to do with banks, while big pawnshop signs were everywhere in towns and cities. Inside the black lacquered gates of these shops were a counter higher than a man’s head, behind which sat cold-blooded greedy usurers. Countless people were stripped to the bone by these money-sharks.

Now pawnshops have disappeared from China. In their place are branches and savings banks of the People’s Bank of China. In Peking alone, there are more than 300. In the first nine months of 1974, in round figures, 164,000 new savings accounts were opened in Peking, 98,000 in Tientsin and 350,000 in Shanghai.

Fankua Lane, Chapei District, Shanghai, was a notorious slum area where 3,800 destitute families lived before the liberation. They dealt with the pawnshops and were tormented by usury. Savings were unheard-of among them. But in the wake of the rapid advancement of socialist construction, this area has changed tremendously. In 1963, many five-storey apartment buildings were put up along the streets. Great numbers of people here are engaged in socialist construction, and their living standards have been moving upward. In contrast with the past, 80 per cent of these families now have banked savings.

“In the old society, I borrowed from pawnshops; now, I have a bank account,” an ex-ricksha puller commented with deep feeling when he made his first deposit. “In the past, I came away with a pawnshop slip; now I have a savings account certificate. Just two pieces of paper, but what a world of difference for us working people!”

In the nation as a whole, the volume of savings deposits has risen without interruption. The 1974 figure was twice that of 1965, and 10 times that of 1952. And 1974 also saw the largest increase in the volume of deposits. Especially worth noting is the ratio of time deposits, which has gone up to 80 per cent. It attests the increasing prestige and the stable value of the yuan as well as the secure life of the people.

Renminbi’s Prestige Grows in the World

The Bank of China, specializing in foreign exchange dealings, has its headquarters south of Tienanmen Square. Before the liberation, this area was part of the “Legation Quarter” where Chinese people were barred from residence. The few banks then operating in Peking all had their offices in the area.

“The value of RMB in relation to foreign currencies has been stable,” Comrade Chen Chuan-keng, who is in charge of the foreign exchange department of the Bank of China, told the writer. “It has never been revalued, up or down. But in recent years, with economic crises worsening in the capitalist countries and monetary crises recurring in quick succession, the exchange rates between major currencies in the capitalist world, such as the U.S. dollar and British pound sterling, have fluctuated continuously, so much so that these governments have been compelled to abandon the fixed official rates and let them ‘float’ with the demand and supply on the money market. To avoid the effects of such fluctuations, the exchange rate of RMB has been changed to guarantee its real value in international dealings.”

The following is a list of foreign exchange rates for the RMB over some years.

| Foreign currency | Average selling and buying rates (in yuan) |

Percentage of increase or decrease | |

| End of Dec. 1971 |

End of April 1975 | ||

| 100 W. German marks | 70.36 | 75.27 | + 6.98 |

| 100 French francs | 44.30 | 43.21 | - 2.46 |

| 10,000 Italian lira | 38.99 | 28.32 | -27.37 |

| 100 Swiss francs | 59.05 | 69.74 | +18.10 |

| 100 British pounds | 590.80 | 420.58 | -28.81 |

| 100 U.S. dollars | 226.73 | 179.13 | -20.99 |

| 100,000 Japanese yen | 736.16 | 608.18 | -17.38 |

“You can see by comparing the exchange rates in this table,” Comrade Chen continued, “that between the two dates, the French franc, lira, pound, dollar and yen went down in relation to the RMB yuan, while the mark and Swiss franc went up. These figures reflect the instability in the value of the various foreign currencies, in accordance with which the adjustments were made.”

“Why have the West German mark and Swiss franc gone up in terms of RMB?” I asked.

“That is because of the appreciation in their value. The value of RMB has not changed.”

“Is the upward adjustment harmful to China?”

“No such problem is involved. Adjustments, upward or downward, are made according to the principle of equality and mutual benefit.”

The stability of RMB has brought it ever-increasing prestige. China’s international payments used to be cleared in terms of a foreign currency. Now, as the currencies of capitalist countries are not stable in value, traders from many countries and regions gladly choose RMB for settling their accounts with China. Since 1968, RMB has played its part in pricing and clearing in the international market, and is used for such purposes by 85 countries and regions in their trade with China. This development is another sign of the long-term stability of RMB.

Making this survey helped me to a deeper understanding of why there is no inflation in China. It is because the country’s economic construction is advancing steadily along the right course that, even though the standard of living is not yet high, the cost of living is stable. When a worker gets on his bicycle and takes his pay home, he need never worry about the devaluation of money cutting into his family’s living. And a housewife getting her dinner ready need not be anxious about tomorrow’s grocery prices. Instead, people think of how to work better at their jobs, or how to learn more so as to build China into a stronger and more prosperous socialist country. Only older parents, in teaching their children the history of China, can personally recall the nightmare of inflation in their own youth.

2

How the Consequences of the Inflation Were Eliminated

TO MOST Chinese past middle age, mention of inflation evokes memories of traumatic experiences before the liberation. The Kuomintang government, politically rotten and economically bankrupt, adopted the policy of unlimited currency issue to make up its deficits and finance its criminal war against the people. A deluge of new “legal tender” currencies—“fabi,” “customs gold units,” “gold certificates,” “silver certificates”—flooded the market, setting prices galloping like stampeding cattle so that they increased several fold, or even dozens of times over, from dawn to dusk.

Worst Inflation in World History

Opening newspapers published in the Kuomintang areas at that time, one is struck by appalling headlines such as:

“Prices Shoot Up Beyond Control; People Horrified”

“Up! Up! Up! Rice Price Passes Million Yuan Mark”

“Cotton Cloth Prices Run Wild; Coal Price Continues to Shoot Up”

On the eve of the liberation of Shanghai in May, 1949, the situation was at its worst, as can be shown by a price list in the publication Shanghai Quotations:

| Retail Prices, Shanghai, May 22, 1949 (In million yuan) | ||

| Rice | 0.5 kilogramme | 1.92 |

| Plain white cloth | 1 chih (1/3 metre) | 1.56 |

| Pork | 0.5 kilogramme | 30.00 |

| Egg | 1 | 2.50 |

| Fish (croaker) | 0.5 kilogramme | 10.00 |

| Green vegetables | 0.5 kilogramme | 1.50 |

More shocking still, the price for a pancake and a fried dough twist, the breakfast staples of the working people, shot up a million yuan on that day. The paper commented: “A pancake and twist cost a million. The only thing the poor can do is to tighten their belts still more and do without.”

An elderly man, infuriated by the skyrocketing prices, counted out, grain by grain, the 0.5 kilogramme of rice he had bought, and calculated that each had cost him 100 yuan. Then he made up a rhyme:

“A hundred yuan for a grain of rice, 150 thousand for an inch of cloth; Chiang Kai-shek, too bad for you; your only road is to hell!”

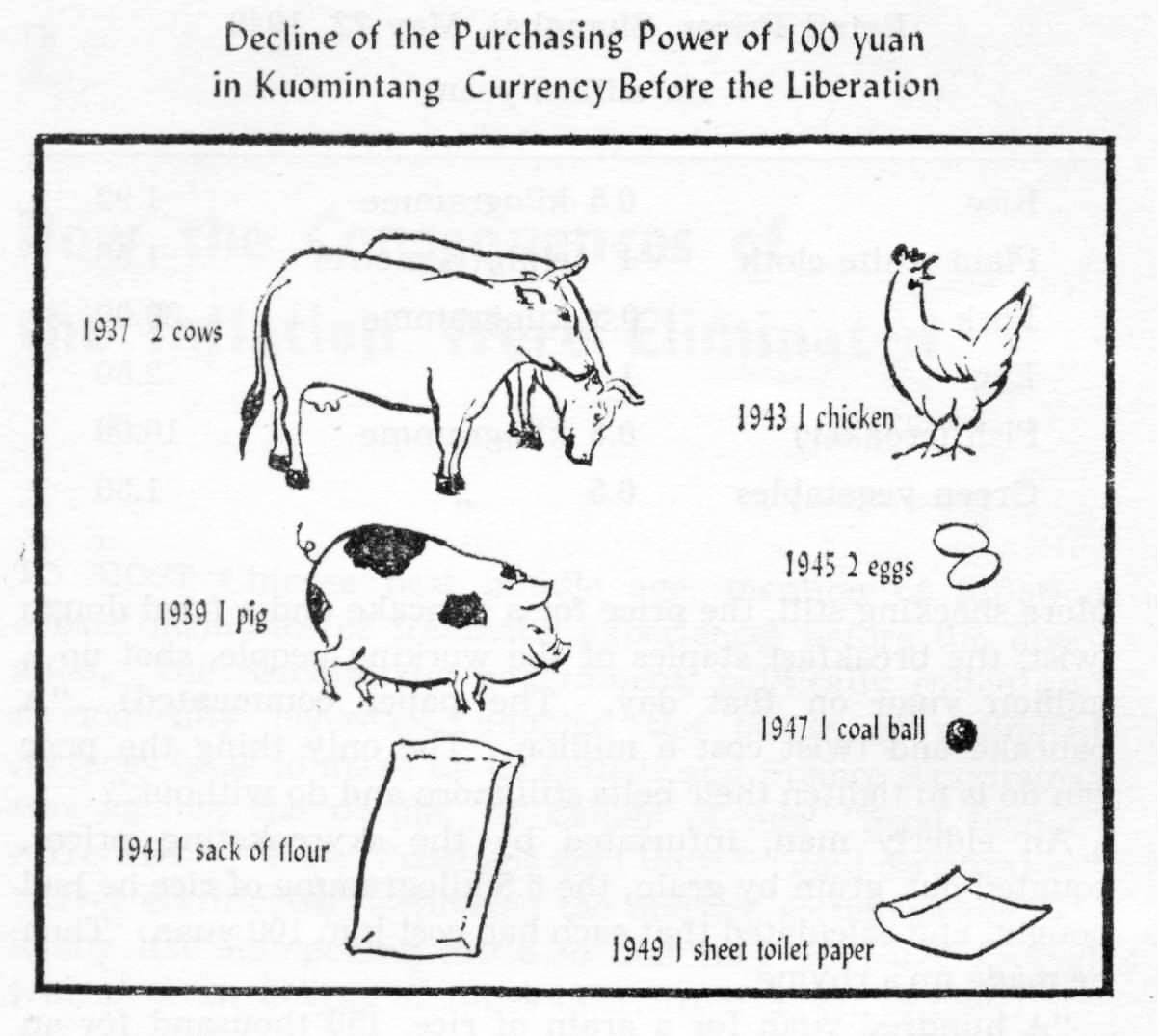

On the next page is a chart based on a revealing table made at that time.

In the twelve years from 1937, when the war against Japanese aggression began, to May 1949, the total amount of bank-notes issued by the Kuomintang government multiplied more than 140,000,000,000 times. At the end of that period, goods procurable in 1937 with one yuan cost some 8,500,000,000,000 yuan. A world record!

The Kuomintang’s phoney legal tender had thus lost all worth in the eyes of the people, who dropped it like a hot brick whenever it came into their hands, converting it at once into goods or some foreign currency. The panic started from Shanghai, spreading rapidly throughout China. “People buy anything they can lay their hands on,” according to one account. “They spend their money as soon as it comes before its value dips further. The first objects of panic buying are eatables.” Although there was a so-called “legal tender,” gold and silver coins or ingots and foreign currencies circulated openly on the rampant black market. In fact, in many places, people rejected the “legal tender,” and wages were pegged to the price of rice or to a foreign currency. In the countryside, transactions in land, houses or other commodities were negotiated in terms of rice or cotton, or through barter; “legal tender” was only used for small change, and was no longer a measure of value or a medium of exchange.

Inflation anywhere is a means of merciless yet covert exploitation of the working people; it is the worst kind of forced government loan or tax imposed on the people. Devaluation of a currency by half would mean doubling the price level, that is to say, the money in any person’s hands loses half its purchasing power, the other half snatched away by the government that issues the bank-notes. This is an exaction which even beggars cannot escape. It was through such extortions that the reactionary Kuomintang government plundered the wealth of the Chinese people to the tune of 15,000 million silver dollars in the 12 years before liberation.

Bankers and commercial capitalists, too, profited from the tempest of inflation. They worked in collusion, hoarding commodities and making wanton profits through sale at exorbitant prices.

Wage earners like factory workers, teachers and professional people helplessly watched their meagre incomes dwindle rapidly in value until they melted to nothing, like snow in the sun. Their sufferings were beyond words.

Many stories current at that time, though they sound absurd to our ears today, were nonetheless bitter facts. One told of a textile worker at Tsingtao in 1948 who, like other wage earners, struggled to get hold of something that would retain the value of his money. Right after being paid, he stood in a queue to buy silver dollars with his paper yuan. While he was waiting his turn, the price shot up by 20 per cent. So he went home in the hope of a better deal the next day, only to find that the price had tripled overnight. Another story concerns professors of the Tsinghua University, living in the outskirts of Peking and their counterparts in Peking University inside the city. At that time it took several hours to travel from Tsinghua to town to shop, so the suburban professors lost out considerably by comparison with their confrères in the city, since prices would rise quite a bit while they were on the way. So even between professors on the same salary scale, there was a considerable disparity if they worked in colleges some kilometres apart. And in Shanghai, soon after the Kuomintang “gold certificates” of 1948 were issued, 61 teachers appealed in the press: “We are desperate! Malnutrition, exhaustion, lack of medical care, inability to support our families and cases of insanity caused by poverty and illness, are common in our lives.” The signatories included university professors. If professors could suffer so, we can easily imagine the plight of the workers and ordinary employees.

A Long-Cherished Dream Comes True

With the founding of the People’s Republic, stabilization of the still fluctuating prices and elimination of the aftermath of the inflation were among the urgent tasks facing the Chinese Communist Party and the new People’s Government.

The Chinese people, who knew so well the bitter taste of inflation, longed for the new government to solve the problem which there had been no hope of solving in the old society. “We must end the inflation,” the millions of China called on it. But the imperialists abroad and reactionaries at home gleefully counted on the inability of the New China to fight off these old evils. They expected that she too would sink irretrievably into the mire of inflation and skyrocketing prices.

Could the newborn People’s Government bring about what the people had long dreamed of, and strike a counter-blow at the enemy slanders and attacks? That indeed was a crucial test for it.

Strengthening the Proletarian Dictatorship

and Hitting the Speculators

After Shanghai’s liberation, silver-dollar dealers still roamed the streets, shouting as they clinked the coins, “Hey, here, gold for silver! Silver for greenbacks! Anyone?”

Pillage and sabotage by the Kuomintang reactionaries before their flight had practically paralyzed Shanghai’s industry, and commodities were critically short. The entire stock of cotton controlled by the People’s Government at the time of liberation would suffice only for a month’s supply to the local textile mills; there was coal for only a week, and its rice stocks totalled only 4.5 million kilogrammes, as compared with the minimum need of 55 million kilogrammes per month. Against this background, treacherous speculators and remnant reactionaries whipped up a frenzied run on gold, silver coinage and foreign currencies, sending prices up again.

The first measure of the People’s Government was to hit hard at the speculators, banning gold and silver coins and foreign currencies from trafficking or circulation, and making RMB the only medium of exchange. Shanghai’s newspapers for days carried headlines voicing the people’s strong demand: “Clear out the silver-dollar dealers!” “Hit the vicious speculators hard!” People paraded with placards inscribed: “Support RMB!” Boycotted by the masses, the coin peddlers had to quit.

But the big-time operators in the Stock Exchange Building were still trying to manipulate prices and stirring up waves in the economy. This centre of speculation of Shanghai’s former bureaucrat-capitalists had more than 300 brokers in various firms dealing in securities, gold, silver, or commodities. Each of their rooms had a battery of private telephones for confidential communications. Manipulated by these gamblers, who ignored the repeated warnings of the People’s Government, gold and silver prices kept soaring, pushing up all other prices. So on June 10, 1949 the Stock Exchange—that centre of crime located in downtown Shanghai—was ordered to close down and 238 leading speculators were arrested and indicted. The 1,800 gold and silver coin peddlers were released on the spot after being enjoined to lead a more honest life. At one stroke, this headquarters of speculation vanished forever from Shanghai.

Speculation also went on in daily necessities such as grain, cotton yarn and piece goods. In Peking, a certain Wang Chen-ting, dubbed “Grain Tiger,” dealt illicitly in grain. Once he defrauded the state stores of 230 sacks of flour for which he raised the price three times a day when re-selling. Upon the demand of the people, the government arrested 16 grain speculators with Wang at their head, and confiscated their stock for sale to consumers at the fixed price. This act won general approbation and applause.

Another, and more important measure against inflation was to keep sufficiently large stocks of commodities such as grain, cotton yarn and piece goods, coal, salt, supplies for industry, etc. in the hands of the state commercial departments to guarantee normal supplies to the market, and make it impossible for speculators to manipulate them. To do so, the People’s Government instituted a national plan of distribution for such stocks. Rice from Szechuan in western China, soybeans from the northeastern provinces, cotton from Shensi in the northwest, coal from the Kailuan collieries in the north flowed into big cities such as Peking, Shanghai and Tientsin.

Less than two weeks after Shanghai was liberated, the new state trade was already active there. It fed into the wholesale market staples like rice, yarn and cloth, and through its hundreds of retail stores, sold them directly to consumers at fixed prices. Underestimating the capacity of the state commercial departments, some speculators hoarded grain they had bought up on the wholesale market, thinking they could exhaust the government’s reserves and then push up prices for their own profit. But the state continued to sell, imposing no limit, so in the end the profiteers themselves were so overloaded with stocks that they had to beg the state commercial departments to buy them back. Grain prices were thus stabilized.

Establishing a Uniform and Independent Monetary System

On May 28, 1949, the day after the liberation of Shanghai, a proclamation was posted throughout the city: “In all liberated areas, as from today, Renminbi issued by the People’s Bank of China shall be the only legal tender. It shall be the sole medium for all tax payments, private and public transactions and price quotations.... The use of Kuomintang gold certificates, gold, silver, or foreign currencies for accounting and clearing is henceforth prohibited....”

The reactionary Kuomintang government had deluged the areas under its control with “fabi,” “gold certificates” and “silver certificates,” in addition to which there were a great number of local currencies issued by landlords and warlords, plus notes and securities issued by private commercial banks. Furthermore, there were U.S. dollars and British pounds, and bank-notes issued by imperialist banks in China. Great numbers of old Chinese silver dollars also circulated. This motley of monies was a powerful stimulant to speculation, disturbing the markets and driving up prices. It served as an instrument for the exploiting classes to squeeze the working people dry.

In our liberated areas, at that time there was also a variety of currencies. It was inherited from the long period in which each of these areas—surrounded by the enemy and separated from each other—issued its own notes (the Border Region currencies) through its own banks.

As soon as a big city (such as Shanghai) was liberated, the People’s Government set about exchanging all Kuomintang currencies for RMB, banned the circulation of all gold and silver coins and foreign currencies, declared the RMB as the only legal tender and forbade its being taken abroad.

At the same time, the People’s Bank of China began to redeem all local currencies that had previously circulated in the various liberated areas. By November 1951 all China was cleared of monetary confusion inherited from the past and a national currency was established. The only remaining exception was the Tibetan local currency, which was eventually redeemed in 1959 after the suppression of the rebellion of the reactionary elements of the upper strata in Tibet.

Centralized and unified currency issue provided the necessary condition for a unified national market in which the supply of money could be planned, and its value stabilized.

More important still, the People’s Government began independently to fix the exchange rates for RMB in relation with foreign currencies and to set up a system of foreign exchange control. Under the reactionary rule of the Kuomintang, not only did the imperialist powers control the lifelines of China’s economy, they also “secured a stranglehold on her banking and finance.” [Mao Tsetung, Selected Works, Eng. ed., FLP, Peking, 1967, Vol II, p. 311.] When China was on the silver standard, the exchange rates for her silver yuan depended entirely on the silver markets in Britain and the United States. Silver coinage flowed out from China in great quantities, bringing about a shortage of money, with consequent deflation that struck hard at national industry and trade. In 1935, on the instigation of the British and American imperialists, the reactionary Kuomintang government abandoned the silver standard and shifted to a paper standard, instituting “fabi,” a legal tender which was not convertible into silver coinage and forced on the people by government decree. It deposited all the gold and silver it had looted from the people in banks in London and New York, pegged “fabi” to the British pound, later to the U.S. dollar, and relied on these foreign currencies for stabilizing the “fabi,” which in the end was turned into a mere appendage of the U.S. dollar. China’s foreign exchange control thus completely fell into the hands of the imperialist powers and their banks in China. In fact, the British, American and other imperialists had turned the country into a dumping ground to which they could shift the burden of their own economic crises. In the period 1935-37, Chinese prices shot up in the wake of fluctuations in the U.S. and Britain. When the price index in Britain went up by 22 per cent, in China their rate was surpassed—it was 34 per cent.

On the eve of the birth of New China, the liberated areas expanded rapidly and gradually linked up into one. In anticipation of the nationwide victory of the War of Liberation, the People’s Bank of China was founded in December 1948 and issued RMB as the national currency to develop the economy and give support to the front. With the founding of the People’s Republic, the country was cleansed of imperialist financial forces. The government established its own foreign exchange rates and control system with all transactions centralized in the hands of the state. All foreign currencies received were to be sold to the state bank, and all purchases and sales had to be handled by it or its agencies; private dealing was outlawed. The unified exchange rates were fixed and announced by the state bank, and they were not pegged to any foreign currency, nor did China become a member of any imperialist monetary bloc. Thus the country asserted complete independence, free of all imperialist control, in managing its currency. These measures helped safeguard China’s sovereignty, made her immune from the impact of economic crisis in the capitalist world, stabilized her money and provided prerequisites for self-reliant socialist construction.

A Unified Fiscal Policy

The imbalance in government finance had contributed to price fluctuations immediately after the founding of the People’s Republic of China. The war of liberation was still being waged. Several million troops were advancing into the southern and southwestern regions to complete the liberation of the country. So military expenditure was still tremendous. In the meantime, with the rapid addition of newly liberated areas, the administrative outlays of the People’s Government grew, but without any concomitant increase of revenue—as industrial and farm production had yet to recover. So there was still an oversupply of money.

The Communist Party and the People’s Government, while making great efforts to stabilize prices, did everything possible to raise production and practise economy. It was determined never to resort to bank-note issue as a solution for fiscal problems.

Among the measures taken, the most important was the nationwide unification of fiscal and economic administration. Right after the establishment of the Central People’s Government in 1949, the greater part of government revenue, cash reserve and supplies was managed by provincial and county governments, with the central government directing only expenditure. The nation lacked a unified fiscal system, and consequently, the revenue and disbursement agencies were not operating in co-ordination. After a unified policy was implemented, all principal types of state revenue went into the state treasury. They included the profits of state enterprises, tax payments by private firms, and the tax in kind from the farming sector. Thus the waste of funds due to decentralization was eliminated. The government also took other measures. It streamlined its agencies and regulated the size of their staff, an effective way of cutting down spending. It enforced more rigid control of cash, requiring all state agencies, organizations, schools, factories and enterprises to deposit their cash in the bank, leaving only a small amount on hand for operating expenditures. Here the purpose was to expedite the recall of part of the currency in circulation. Meanwhile, the government ensured a large supply of goods by improving the functioning of commercial establishments and taking inventories of their stock for distribution according to the overall plan of the state. Thanks to all these measures, the economic situation throughout China took a quick turn for the better and the state budget was balanced the very next year.

Gone was the inflation that had lasted for twelve years prior to liberation, and the people rejoiced at the realization of their cherished dream. All this was achieved in half a year, from November 1949 to March 1950. Afterwards, the seemingly insatiable “buying power” on the speculative market disappeared and prices, instead of rising, began to fall. People said in amazement that this was a miracle in China’s modern economic history.

3

What Is the “Secret” of Renminbi’s Long-Term Stability?

AFTER THE triumph over the left-over inflation in 1950, Renminbi underwent other crucial trials: the War to Resist U.S. Aggression and Aid Korea (1950-53), the three years of severe natural calamities (1959-61) and continuous disruption and sabotage by class enemies from within and without. It is quite usual, in war or in economic troubles, for a government to rely heavily on the issue of paper money for its spending, with the result that its currency depreciates. Not so with New China, nor with Renminbi, which has withstood all onslaughts, maintained its value, and acquired growing world-wide prestige.

It was difficult enough for New China to accomplish the feat of ending the 12-year-old inflation, and an even more arduous task to afterwards keep her currency stable for a much longer period. How has she done it? The factors are many. We shall discuss only a few basic ones here.

The Socialist System Is the Safeguard

As is known, stability in the purchasing power of money is closely related to the supply of goods. When money is in oversupply in relation to goods in the market, its value is bound to fall; when the money in circulation and the supply of goods are in balance, money tends to remain stable in value.

Under capitalism, the means of production are owned by individual capitalists and production is anarchic. On the one hand, currency issue is not amenable to planning. On the other hand, the supply of goods is controlled by capitalists who seek the maximum profit, and so try every means to keep monopolistic prices high, preferring to destroy their stocks of goods, if necessary, rather than sell them to the working people at low, stable prices. Therefore, inflation is an incurable disease in capitalist society.

In contrast, China is a socialist country under the dictatorship of the proletariat In their victorious revolution, the Chinese people, led by Chairman Mao and the Chinese Communist Party, overthrew imperialism, feudalism and bureaucrat-capitalism—the “three big mountains” that had lain upon them like a dead weight. All factories, enterprises and banks owned by bureaucrat-capital were nationalized. Then came the socialist transformation of agriculture, handicrafts and capitalist industry and commerce, converting them from private to socialist enterprises under state or collective ownership. This done, the state became dominant in the economic life of the nation. Socialist public ownership took the place of capitalist, private ownership, and the economic basis of exploitation of man by man was done away with.

The building of a socialist system enables China to conduct the production, circulation and distribution of commodities, as well as currency issue, under a unified state plan. Production is no longer aimed at making profits or confined to what is profitable. Instead, it serves socialist construction and satisfies the needs of the people. The amount of goods to be produced by the factories, the amount to be put on sale in the shops, the volume of currency issue—all are set by annually-made state plans and kept in overall balance. The state thus regulates the supply of money on the one hand and plans the marketing and pricing of goods on the other. The achievement of this equilibrium stabilizes currency and uproots inflation at its very source.

The Key: A Growing Socialist Economy

A stable currency needs to be backed by an ample supply of goods. The latter, in China, depends on the growth of the socialist economy. That is to say, an increasing volume of goods is made available through the growing productivity of socialist industry and agriculture. Only thus can the stability of a currency be guaranteed.

Renminbi is backed by a certain amount of gold and foreign exchange reserves within China, but its strength rests mainly upon the great volume of goods in the hands of the state. Hence, the key factor is the continuous development of industry and agriculture—the expansion of the socialist economy.

While promoting production of producers’ goods such as steel, coal, petroleum, etc., China takes great care to increase the supply of consumer goods such as cloth, edible oil, sugar, etc. and keeps the output of such goods in balance with the overall demand of society, thereby maintaining an equilibrium between the quantity of money in circulation and the supply of consumer goods on the market. Through the sale of these goods, the state recalls the money disbursed for farm products and wages. Meanwhile, since consumer goods are produced mainly by the sectors of agriculture and light industry, and producers’ goods by the heavy industry sector, a proper proportion must be maintained among these sectors, too.

Agriculture is the foundation of China’s economy and the mainstay of her currency because the bulk of the raw materials for the staple consumer goods (edibles, clothing, articles of daily use) and for light industry comes from the agricultural sector. With a flourishing agriculture, there is a greater quantity of grain on the market and the raw materials for light industry are more abundant. All this ensures an ample supply of goods to back the currency and achieve a balance between the quantity of money and the volume of goods in circulation.

Since the founding of the People’s Republic, China has followed the policies of taking agriculture as the foundation and industry as the leading factor and developing the economy and ensuring supplies. Her economy has continually grown. Grain output has increased 2.4 times, from 110,000,000 tons in the early post-liberation years to 250,000,000 tons today. Industrial crops—cotton, vegetable oil, sugar, hemp, tobacco, tea, etc.—have also increased greatly. On the basis of the rapid growth of agricultural production, industry, too, has developed strikingly. Old China had almost no heavy industry to speak of, except for some light industry, colonial or semi-colonial in nature, in the coastal provinces. Since liberation, China has built up and expanded her metallurgical, petroleum, coal, machinery, chemical, construction-material and other industries, as well as further developed her light industry. Since the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, the growth of her industries has been especially marked, and in 1974 the gross value of their output was 2.9 times that of 1964. As compared with the years immediately after the liberation, the supply of all kinds of consumer goods such as meat, fish, poultry, vegetables, fruit and other farm products, and industrial goods like cloth, paper, sugar, cigarettes, medicines, bicycles, sewing machines, radios and so on, increased several-fold, and for some items tenfold or more. The volume of the nation’s retail sales in 1973 was more than 7 times that of early post-liberation days. Stocks on hand at the end of June 1974 were double those of the same month in 1965. Thus any increase in the quantity of money in circulation is backed by a concomitant increase in the market supply of goods, thereby ensuring the long-term stability of the Renminbi.

The Circulation of Money Is Planned

To achieve balance between the purchasing power of society and the supply of goods, currency issue is placed under centralized, unified control by the state. Renminbi is issued only by the state bank; no region, unit or person is allowed to issue currency. For better control over money circulation, all government agencies, organizations, factories and enterprises are required to deposit their cash in the bank, leaving only a stipulated amount in hand. Big transactions among them are cleared through the bank; the use of cash in such transactions is not allowed. No notes or securities may circulate, so stock-market speculation, common in capitalist countries, does not exist in China.

The state bank regulates the supply of money according to plan to ensure its normal circulation.

The spending, which is controlled by the state and calculable, falls into four main categories: (1) payment of wages; (2) payments for farm products; (3) administrative and welfare expenses of government agencies, social organs, enterprises, etc.; (4) state grants and loans to rural people’s communes, social relief funds and so on. All this money eventually turns into social purchasing power.

Materiel and raw materials needed by state factories and other enterprises for production or capital construction are allocated by the state under a unified plan, and payment for such transactions is generally settled through the bank without using cash.

The currency reverting to the state is also calculable. It is recovered through three main channels: (1) income from sales of goods by state enterprises; (2) receipts from public services and utilities such as railway and bus fares, movie admission, charges for water and electricity, etc.; (3) private deposits, and farm loans paid back to the state.

The state controls the flow of money into the market and its recovery, and has the relevant figures at hand. Therefore, it can use planning to maintain a rough balance between the money in circulation (purchasing power of society) and the volume of goods available. For example, each year before the state decides on the number of new workers and employees, an estimate of the additional wage-outlay is made. When this is added to the existing outlay for wages, the state sees to it that an adequate supply of goods is made available so that the additional money in circulation is retrieved through the sale of goods.

Similarly, to recall the money expended in the purchase of by-products from the countryside or in farm loans, the state provides the rural areas with adequate manufactured consumer goods and producers’ goods for agriculture.

Adjustments are made for any temporary imbalances between the supply and recall of money. Measures to this end are: (1) If there is a temporary oversupply of money, the state trading agencies put more goods into the market out of their stocks to hasten the backflow of money. (2) If the amount of goods on the market calls for a greater quantity of money, the state bank expands its credits and puts more money in circulation. In the contrary case, the bank cuts down its loans and recalls part of the money in circulation. (3) State fiscal policy is another lever. It regulates the loanable funds of the bank so that the latter can increase or contract its credit operations to adjust the supply of money.

Naturally, unforeseen situations constantly emerge. Balance is relative and imbalance is absolute. When temporary imbalance arises in some departments, the state makes an immediate readjustment in its planning to achieve a new balance.

Unified Price Management

In China, price management is exercised by the local authorities at various levels under the unified leadership of the central government.

In capitalist society, the scale of prices and profits determines production as well as consumption. “Production of surplus-value is the absolute law of this mode of production,” as Karl Marx revealed. [Karl Marx, Capital, Eng. ed.., Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow, 1954, Vol. I, p. 618.] Profit is what the capitalists are after; when the supply of goods falls short of demand they raise prices, and vice versa. Hence price fluctuations are unavoidable and production is always blind. In this situation, money cannot be stable.

In socialist China, it is also necessary to keep a balance between commodity supply and demand to achieve price stability. But the rise or fall of prices does not lead to blind expansion or contraction of production. Here production is governed by plan and by pre-determinated proportions.

As already stated, in China, with her public ownership of the means of production, industrial and farm goods are produced by socialist enterprises owned by the whole people or those collectively owned by the working people which include the rural people’s communes. The aim of production is no longer private enrichment but the growth of the socialist economy and the satisfaction of the people’s needs. Production is not blind but conducted according to the plan of the state. The state controls the bulk of the products because it owns all those made by the state enterprises, and purchases all marketable farm produce from the rural people’s communes at unified, reasonable prices which it sets. So, goods at all stages, from production to distribution, are subject to unified state planning.

For the commodities vital to the national interest and to the livelihood of the people, such as steel, coal, petroleum, grain, cotton piece goods, etc., the appropriate administrative organs of the central government set the prices at every stage—procurement, transfer or retail sale.

Prices for ordinary products are locally fixed and regulated in accordance with rules issued by the central government, some at the provincial, municipal or autonomous region level, and others at the level of the prefecture or county.

For highly perishable goods such as vegetables and fruit, the central or provincial organs concerned set only the general price level for procurement and sale, the range of seasonal price differentials, the range of price differentials based on quality, and the general principles in price administration. As to the actual fixing of prices, seasonal differentials are decided at the county level, and adjustments for quality differences are made by shops at the grass-roots level.

This is how, in China, an end has been put to blindness in production and to the fluctuation of market prices.

When, as sometimes happens, the supply and demand for certain daily necessities get out of gear, the state never raises prices since that would be against the interests of the working people. Instead it relies on reasonable rationing while augmenting the supply of the goods concerned to restore the balance as quickly as possible.

With regard to non-essential goods, if a temporary imbalance between supply and demand occurs, arrangements to increase their production are also made, but prices are sometimes raised.

Yet, even when prices for these goods are marked up, those of other goods are lowered. The reason is that, since the total of goods put on the market is kept in balance with the total purchasing power at a given time, the inadequate supply of some goods is accompanied by an oversupply of some others. Here, the two-way price adjustments, up and down, are combined to maintain a stable general price level and stability of the value of currency.

Steadfast Policy of Fiscal Balance

Fiscal balance is the consistent policy in the period of socialist construction in China, by contrast with the situation under the reactionary Kuomintang government which relied on the printing press to cover its deficits.

Then, the Chinese people were being squeezed dry by the combination of imperialism, feudalism and bureaucrat-capitalism. From the middle of the 19th century on, the imperialists often invaded and plundered China. In the Sino-Japanese War of 1894 and the armed invasion by the allied forces of the eight powers in 1900 alone, they robbed her of 20,000 tons of silver which China was forced to pay in indemnities. And in the 22 years from 1927 to 1949, the “four big families” of the bureaucrat-comprador class that was an appendage of imperialism—the families of Chiang, Soong, Kung and Chen—extorted from the Chinese people a sum equivalent to more than 15,000 tons of gold. Moreover, prior to 1949, exploitation by the feudal landlord class, the other prop of imperialist rule in China, ground more than 35 million tons of grain a year out of the peasants in land rent. All this, Plus the general corruption and the wasteful, extravagant living of the reactionary Kuomintang rulers paralysed the nation’s economy and brought ever-growing budgetary deficits, which in 1936 had risen to 74 times the 1927 figure. And from 1937 to 1947, deficit spending averaged 70 per cent or more of the total budget. This was covered solely by the issue of paper money, with rapid currency depreciation and skyrocketing price levels resulting. The purpose of these rulers, along with the continuous fattening of the bureaucrat-capitalist class, was to squeeze even more wealth out of the working people to support their big military machine for war against the people and perpetuate their reactionary rule.

The birth of the People’s Republic of China, independent politically and economically, ushered in a new era in government finance, marked by the balance of revenue and expenditure. Chairman Mao pointed out at that time: “The balance of revenue and expenditure ... should also be consolidated.” [“Fight for a Fundamental Turn for the Better in the Financial and Economic Situation in China,” New China’s Economic Achievements, 1949-1952, China Committee for the Promotion of International Trade, Peking, 1952, p. 7.] He stressed three links in achieving this: growth in production, the practice of economy, and ample reserves. Earlier, he had said: “To increase our revenue by developing the econoxny is a basic principle of our financial policy.” [“Our Economic Policy,” Selected Works, Vol. I, p. 144.] This principle takes the growth of production as one of the keys to securing a balanced budget. For more than a quarter-century, China has relied on her own strength to vigorously develop industrial and agricultural production, and provide large sums for capital construction. Fiscal revenue is now more than a dozen times that in the early years after liberation. The revenue from state enterprises then comprised only 34.1 per cent of the total. Today it amounts to around 90 per cent, precisely as a result of implementing this principle.

In accumulating funds for financing the growing economy, New China has never piled added burdens on the people. There is no personal income tax. For urban residents, there are only licence fees for bicycles and motorbikes and a tax on privately-owned housing, both very low. In the rural areas, the amount of the agricultural tax is fixed and does not rise with increased production. It now averages only 5 per cent of total farm output as compared with 12 per cent in 1952, and represents a very small part of the total revenue of the state.

Practising thrift is one of the basic principles in the socialist economy and another key factor in securing fiscal balance. On this principle, expenditure is kept in balance with revenue in the annual budget; deficits are strictly prohibited. In implementing the budget, the practice of economy and elimination of waste are promoted so as to get more results with less funds. It is in this spirit that the workers and staff of the Taching Oilfield have both increased production and reduced costs each year. Taching’s total contribution to the state treasury during the last 13 years amounts to a total 10 times the investment by the state in this enterprise.

The bulk of government spending is for the development of the socialist economy, culture and education. High on the economic priority list comes large-scale capital construction needed for the expansion of industrial and agricultural production. Current annual investments by the state in capital construction alone amount to several times the total annual fiscal revenue of China in the early post-liberation period. In the ten years from 1964 to 1974, more than 1,100 large and medium-size enterprises were completed. Many enterprises are highly meticulous in the designing and construction of their plant, and thrifty in their spending. For example, the power plant at Minhang, Shanghai, was completed in less than ten months from the drawing-board to actual operation, shortening the originally planned time by half a year and saving more than 10 million yuan in investment. It achieved the goal of setting up the enterprise from beginning to end within a year.

In order to channel more funds into productive construction, all non-productive outlays are strictly controlled by the state. For instance, the construction of office buildings, assembly halls, hostels, etc. is thus controlled. So are procurements made by government agencies, enterprises and military units.

In the annual final account of revenue and expenditure, there is generally a small surplus. By the beginning of 1965, the country had paid off all its external debts, a year ahead of schedule, and by the end of 1968, the government had redeemed the last of its public bonds. Today, China presents the spectacle, unusual in the world, of a country with neither internal nor external debt.

Another key factor in China’s balancing of her budget year after year is her fiscal reserve. It consists chiefly of the following: (1) A certain proportion of the budget set aside as a contingent fund. In 1955, for example, this amounted to 3.42 per cent of total budget expenditure; in 1956, it was 2.57 per cent, which became the approximate standard for the later years. (2) Budgetary surplus in most years. (3) The stock of goods in the hands of the state, which is in fact another form of fiscal reserve. This stock is continuously augmented by the constant strengthening of the country’s economy and finances.

Under extraordinary circumstances, as during a year of natural calamities, adjustments are made to secure a balanced budget through greater efforts in production, the practice of economy and the use of fiscal reserves.

These are further ways of keeping the quantity of money in circulation within the bounds of the level of production and the needs of commodity circulation in the market. There is no need for the state to resort to the emission of paper money to make up for the deficits. Hence, too, the stability of the value of currency.

Balance of Credit

The People’s Bank of China is the sole source of loans in China. Mainly, it provides short-term credit for industrial and commercial establishments, or for the development of the collective economy of rural people’s communes. The funds of the bank from which loans are made come from three sources: (1) deposits by factories, enterprises, government agencies, organizations and collectively-owned units; (2) personal savings deposits in town and country; and (3) the bank’s own accumulations.

The amount of loans made is determined by the need arising from the growth of production and the expansion of the market. When the need for loans is higher than the bank itself can meet, the state financial organs may make new appropriations to bridge the gap.

Under China’s socialist system, all loans, settlements of account and larger cash payments between various enterprises must go through the state bank, and no lending and borrowing, sales on credit or forward buying or selling are allowed between these units. The state bank extends only short-term loans needed for production and circulation of goods. The borrowers are not allowed to use the money for capital construction or the purchase of such equipment as would tie up the funds for a long time. In this way, through deposits and loans, the state bank controls the money supply, keeping it roughly in balance with the volume of the flow of goods, and ensuring a stable currency.

Differential Pricing for Domestic and Foreign Markets

The long-term stability of Renminbi and its credit standing in the world markets also stem from China’s success in balancing her foreign trade and international payments.

China’s foreign trade was formerly monopolized by imperialist powers and their lackeys, the bureaucrat-bourgeoisie. The imperialists enjoyed privileges based on the unequal treaties through which they had forced China to open up “trading ports,” and also on their control of China’s customs service as well as establishments dealing with insurance, navigation, wharfage, warehousing, etc. They plundered China by buying up her farm products at absurdly low prices and selling industrial goods to her at exorbitantly high prices. By such unequal trade, they made excessive profits, causing chronic adverse imbalance in China’s international payments and foreign trade, which was virtually reduced to a suction-pump draining the Chinese people of their blood.

In New China, foreign trade is controlled by the state. All imports and exports are subject to the state plan, and all transactions, from day-to-day operation to the clearing of accounts, are handled by the foreign-trade agencies of the government.

Giving effect to the policy of independence and self-reliance, China plans her imports and exports on the basis of the needs of the nation’s economy and of what is currently feasible. The principle of maintaining balance in foreign trade and international payments is strictly adhered to. Gone forever is the time when the country was flooded with foreign goods and the Chinese people suffered from ruthless exploitation by the imperialist powers through unequal trade. There is no trace now of the old situation in which enormous adverse trade balances exhausted China of her gold and foreign exchange reserves, and the country was weighed down by foreign debts which, in turn, caused disastrous depreciation of currency and the spiralling of domestic prices.

The overwhelming majority of manufactured goods used in China is now domestically produced, and her internal market is vast. Her trade relations with more than 150 countries and regions throughout the world are carried on under the principle of equality and mutual benefit, with each partner making up what the other lacks—a principle which has enhanced the amity between New China and the people of these lands. But the main emphasis is on the domestic side. Home production supplies most of her goods, and sales are made mainly to her own people, especially the masses of peasants. On this home market, prices remain immune from the impact of fluctuations on the world market.

Furthermore, China practises differential pricing for domestic and foreign markets. Imports sold on the domestic market are priced the same as similar home products of the same grade without following fluctuations in the world market. As for goods for export, all are purchased at the domestic price level, independently of the price fluctuations of these goods in the world market. But they are sold abroad at the international market price, following its fluctuations. Thus China’s domestic prices are kept basically independent of the world market, guarding the stability of her currency.

* * *

In China, the people at large are now so accustomed to a stable currency that they take it for granted. Anyone asked the reason is likely to reply: “Well, it’s because we’re a socialist country.” That is indeed true. The socialist system, with its economic planning, is the cornerstone upon which the stability of RMB rests. This is the prerequisite for the success of all the measures described above. It can be called the real “secret” of the long-term stability of China’s currency.

Marxist Political Economy Home Page on MASSLINE.ORG

MASSLINE.ORG Home Page