CELL-PHONE ADDICTION

[Or, more generally, “digital addiction”.]

“Next, there’s our cell-phone addiction. American adults spend around

3 ½ hours on their devices each day, trying to keep up with the volume of emails,

texts, social-media updates and 24/7 news. And much of our time is ‘contaminated

time’—when we’re doing one thing but thinking about something else. Trying to get more

miles out of every minute—scanning Twitter while watching TV, for example—makes us

think we’re being productive, but really it just makes us feel more frazzled.”

—James Wallman, “TheView Opener”,

Time magazine, Feb. 10, 2020, p. 14.

“When work is interrupted by a digital distraction like a message, it

takes 23 minutes on average to return to the original task, according to one study.”

—“A Guide to Tech Use in the Hybrid

Workspace”, New York Times, June 24, 2021.

“Portion of teenage drivers in the United States who say they often take

‘long glances’ at their phones while driving: 7/10 [Source: Rebecca Robbins, Harvard

University (Cambridge, Mass.)]

“Chance that the average teenage driver

is looking at their phone at any given time while driving: 1 in 5 [Source: Ibid.]

—Harper’s Index, November 2025, online

at: https://harpers.org/harpers-index/

CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY (CIA)

The most important of the many intelligence and covert operations agencies of the United

States government. It is notorious for overthrowing elected governments in other countries

(such as in Iran in 1953 and Guatemala in 1954), for assassinations, torture and virtually

every other crime that can be thought of, all in the service of U.S. imperialism.

The CIA is also notorious for its

incompetence and stupidity when it comes to actually gathering intelligence! It failed to

foresee the collapse of the state-capitalist Soviet Union or the 9/11

attack by Al Qaeda, for example. It failed to take seriously China’s repeated warnings that

it would enter the Korean War if the invading U.S. troops pushed close to the Chinese border.

One ex-CIA analyst noted that “In 1979, the CIA’s highest-ranking analyst, Robert Bowie,

testified to Congress that the shah of Iran would remain in power, that Ayatollah Khomeini had

no chance to take over, and that Iran was stable.”

Its faulty intelligence and planning led to the abject failure of the Bay of Pigs Invasion

in Cuba which attempted to overthrow Fidel Castro in 1961. One of the major reasons for its

continual intelligence failures is that the CIA is comprised of people who actually believe

much of the endless political propaganda and wishful thinking put out by the U.S. government

and the ruling class media.

The death toll incurred by CIA activities

and by governments that have been installed with the help of the CIA runs into the millions,

with covert operations ranging from Indochina, Indonesia, Latin America and Africa which

include horrific episodes of torture and political persecution. A recurring CIA specialty

seems to be to support forces that later turn against the U.S. government and that must

then be “neutralized”. This phenomenon is part of the more general category known as

“blowback”. For example, Osama bin Laden and his Al Qaeda

organization that carried out the 9/11 attacks against the U.S. in 2001 was originally funded

and trained by the CIA as part of its

covert war in the 1980s against the Soviet social-imperialist occupation of Afghanistan.

CIA activities are occasionally

“investigated” when some information about them comes to light, with some minor reforms or

reprimands enacted. But these are at most cosmetic and invariably totally ineffective, as

demonstrated by the revelations of still more nefarious activity later on. The CIA has been

nicknamed “Capitalism’s International Army” (among other more unflattering titles, like

“Cocaine Import Agency”, for its purported role in starting the inner-city “crack” cocaine

epidemic) and the operatives of the agency (at least of its covert activities wing) are highly

indoctrinated servants of American capitalism who see themselves as its guardians. The CIA

is currently involved in activities throughout the Middle East and the Horn of Africa,

where it is busy trying to subdue local Islamist militias and terrorist groups (i.e., those

who threaten U.S. strategic designs on the region). One particularly ugly aspect of this

activity is the kidnap and torture flights known as “renditions”,

where suspects are flown to countries where torture is routinely practiced. —L.C.; S.H.

See also below, and:

“BRAINWASHING”,

COVERT ACTION,

“MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE”,

MKULTRA,

“MUSHROOM THEORY”,

PHOENIX PROGRAM

“CENTRAL PROBLEM” OF THE MARXIST-LENINIST-MAOIST THEORY OF ETHICS

In his magnificent work, Anti-Dühring Engels

presented the reasons why we hold that each class in class society has its own separate morality.

And each class morality is based on the interests of that particular class; that is, on those

things which collectively benefit the members of that social class. The question then

arises, however, what makes one class morality—that of the revolutionary proletariat—better

than that of another class morality, such as the morality of the bourgeoisie? This question

is what has been called (especially by bourgeois critics of Marxism) “the central problem of

Marxist-Leninist ethics”. Although this question is relatively easily answered, because of its

importance in fully understanding MLM ethics we will present a fairly long discussion of the

issue here:

There is one little puzzle which often serves as a road block for people

considering communist morality, and which is sometimes called the “central problem” of

Marxist-Leninist ethics by bourgeois philosophers. (It is not just anti-Marxist philosophers

who raise this point however; I’ve heard it from the masses as well.) The gist of it goes

like this: “You say each class has its own morality, its own ideas of what is right and

wrong, and that such questions can only be answered in terms of class moralities. But then

you say that communist morality is better than bourgeois morality, a moral judgment

which can only be made convincingly from outside any specific class morality. (After

all, the bourgeoisie can claim that their morality is “better” too.) Obviously you haven’t

thought out your position very well.” This little conundrum can be fairly easily dealt with,

but I have yet to see any fully satisfactory resolution of it in print.

In Anti-Dühring, for example,

Engels attempts to resolve the problem this way (after introducing the three main European

moralities of the age, Christian-feudal, bourgeois, and proletarian):

“Which [morality], then, is the true

one? Not one of them, in the sense of absolute finality; but certainly that morality which

contains the most elements promising permanence, which, in the present, represents the

overthrow of the present, represents the future, and therefore the proletarian morality.”

[Peking, 1976, p. 117]

There are really two, somewhat

incompatible, principles here: 1) That morality is best which has the largest number of

lasting elements, and 2) That morality is best which represents the future. Note first that

both these ethical principles are extra-class; that is, neither really has a class basis.

And in fact it is completely true that no principle for choosing among class

moralities can be class based. If it was, it would be begging the question. Note secondly,

that no real argument is given for either of these two principles. Why in fact should we

accept them? How do we know that some other principle is not superior? Actually, I can’t

accept either principle as it stands, though I recognize that there is an element of truth

to each.

Consider the first principle, that the

best morality today is the one which has the largest number of lasting elements. If that

were really true then the best morality today would already be the morality

appropriate in the future. But the best morality today (proletarian revolutionary morality)

is not in fact identical to the morality of the communist society of the future. To mention

just one example, one that Avakian also alludes to, I am sure that in communist society,

capital punishment will not exist; it would be wrong. But as Avakian correctly notes, the

masses will not be able to advance to that situation unless some of the worst bourgeois

representatives are executed in the course of the revolution. Once you recognize that

present-day proletarian morality is not identical to the morality of communist society of

the future, you are already implicitly granting that Engels’ first principle cannot

be fully correct. If it were, we would have to try to do the impossible—implement today a

form of morality appropriate to the future.

Engels’ other principle isn’t completely

correct either; the best morality is not necessarily the one that “represents the

future”. The future is not always preferable to the past; Nazi Germany was not preferable to

the Germany of Engels’ day. And bad as the bourgeois morality of Engels’ day was, Nazi

“morality” was clearly worse. At this point in history, it is not even possible to be

absolutely certain that humanity has a long-term future. Until capitalism is completely

overthrown the serious possibility remains that it will destroy humanity completely, quite

possibly in some future nuclear Armageddon, or perhaps through some environmental catastrophe.

It is no longer possible to have the unqualified long-term optimism that Marx and Engels

showed. The reality of today is much more desperate (even with the temporary respite due to

the collapse of one of the two major imperialist superpowers [Soviet social-imperialism])—which

makes proletarian revolution all the more necessary and urgent.

Lenin suggested Engels’ approach when he

said: “Morality serves the purpose of helping human society rise to a higher level and rid

itself of the exploitation of labor.” [LCW 31:294] This of course is true, but it apparently

fails as a principle for choosing among class moralities. The reason is simple: saying

one form of society (communism) is “higher” or better than another form (bourgeois) seems to

just be expressing a class attitude of the revolutionary proletariat, and not an extra-class

judgment.

So what then is the answer? On what basis

can we choose among class moralities? We can turn to Marx and Engels for a hint. In The

Holy Family, they remark (in pointing out the limits of the great French materialist

philosophers of the Enlightenment) that “If correctly understood interest is the principle of

all morality, man’s private interest must be made to coincide with the interest of humanity.”

Carrying this idea a step further, in class society, the interests of one class must be made

to coincide with that of humanity as a whole. Fortunately, this can in fact be done: any

immediate selfish interests of the proletariat (yes, there are some) must be discarded, and

the resulting long-term, true interests of the proletariat then do coincide with that of

humanity. Lenin once remarked (I forget where) that even the interests of the working class

must give way whenever they really come in conflict with that of humanity as a whole. The

class interests, and thus the morality, of the proletariat, properly understood, do in fact

represent the interests of humanity. Of all the classes and strata that exist today,

only the revolutionary proletariat seeks to abolish all classes, including itself, and

restore the harmony of interests among humanity that is necessary for there to be a

single human morality. That’s why proletarian morality is better than any other class

morality.

Although many well-intentioned people

imagine otherwise, in class society the interests of humanity can only be championed via the

interests of a class, the one class whose interests can be made to coincide with those

of humanity as a whole, and that is the revolutionary proletariat.

The key concept in resolving this

conundrum of choosing among class moralities is once again that of interests, but now

the interests of humanity as a whole. As I said before, it is impossible to overemphasize the

importance of the concept of interests in ethics. But some Marxists may still be a bit

uncomfortable with my resolution of the conundrum. Lenin insists, in The Tasks of the Youth

Leagues, that “We reject any morality based on extra-human and extra-class concepts.”

[LCW 31:291] But here I am using an extra-class principle (though not an extra-human one) to

decide among class moralities, and even insisting that only an extra-class

principle can accomplish this—if the reasoning is not to be circular.

I have found that it is helpful to

recall the general overall history of human morality at this point. Morality first arose in

primitive-communal society where there were no classes, and at that time it was based on the

common, collective interests of the whole group (tribe or whatever). Class moralities arose

later when, with the advent of slavery, most of those common, collective interests ceased to

exist. When common interests were split asunder, morality had of necessity to be split asunder

as well. Only when humanity completely regains all these common, collective interests will it

be possible to once again have a unified human morality. And this is only possible if one

single class gains total ascendancy and transforms itself, along with the remnants of all

other classes, into a unified classless humanity. No exploiting class, of any variety, can

possibly do this, because obviously every exploiting class needs another class to exploit. No

exploiting class wants for one minute to get rid of social classes! Only the modern exploited

class, the proletariat, can accomplish this, because only the proletariat truly has an

overriding interest in getting rid of all classes, transforming even itself.

Moreover, it is useful to think about

what must have happened when the common, collective interests of primitive-communal society

were split. Did this mean that humanity then had no common interests whatsoever? No,

the split-up was not that extreme. When slavery arose, the once common interest in seeing

everyone in the group prosper no longer existed; the slave owner no longer gave a damn about

whether his slaves prospered; his only concern for his slaves was that they remain healthy

enough to work hard for him. The slaves, in turn, had no interest in seeing the slave owner

prosper; their interests lay more in seeing him dead. But both the slave owner and the slaves

did have a residue of some common interests. Both had at least some common interest in the

continued health of the slaves, though for drastically different reasons. As another example,

both had an interest in the continuation of humanity as a species.

When we say that in class society there

must be separate class moralities because there are basically incompatible sets of class

interests, we are not denying that there is also a slight residue of abstract universal

(above-class) human interests common to all classes. It is because such a residue of

abstract universal interests still exists that we can talk about such things as the “common

elements” in various class moralities (as Engels does). Thus all class moralities say that

murder is wrong in the abstract; but slave owners did not believe that killing a slave was

“murder” or morally wrong, nor did any enlightened slave think that killing a slave owner was

murder or wrong. Similarly, the modern bourgeoisie does not really believe that killing

rebellious workers in the home country is wrong, nor do they view it as wrong to kill

rebellious people of any class in foreign countries under their thumb. And the revolutionary

proletariat does not view it as wrong to kill some of those bastards if that is what it takes

to get rid of their rule. In short, the prohibition against murder is a “common element” of

the two hostile class moralities only if expressed in the abstract, and not when you get down

to the specific content involved. So what good then is this abstract residue of common

interests, and common morality, that all classes can agree on? It is of no use whatsoever in

practice, and that is why there needs to be separate class moralities. The abstract residue

of universal human interests, and a universal human morality, has in fact only one valid

use—namely, in deciding which of the various competing class moralities is the best, or

in other words, which class morality comes closest to the abstract ideal now (here is the

echo of Engels’ view), and much more importantly, which can eventually lead to a universal

merging of all the most basic interests of everyone, with a new universal human morality

erected on that base (here is the echo of Lenin’s view).

This so-called “central problem” of

Marxist-Leninist ethics, does in fact provide a serious obstacle for many who might

otherwise accept our class-based point of view. That is why we need to get clear on just

why this is not really a genuine “problem” for MLM ethical theory.

—Scott Harrison, adapted from his

“Review of Bob Avakian’s We Need Morality, But Not Traditional Morality”, Jan.

23, 1996, which is available in full at:

https://www.massline.org/Philosophy/ScottH/Avaketh.htm

CENTRALISM AND DEMOCRACY

See also:

DEMOCRATIC CENTRALISM

“In 1957 I said: ‘We must bring about a political climate which has both

centralism and democracy, discipline and freedom, unity of purpose and ease of mind for

the individual, and which is lively and vigorous.’ We should have this political climate

both within the Party and outside. Without this political climate the enthusiasm of the

masses cannot be mobilized. We cannot overcome difficulties without democracy. Of course,

it is even more impossible to do so without centralism, but if there’s no democracy there

won’t be any centralism.

“Without democracy there cannot be any

correct centralism because people’s ideas differ, and if their understanding of things

lacks unity then centralism cannot be established. What is centralism? First of all it is

a centralization of correct ideas, on the basis of which unity of understanding, policy,

planning, command and action are achieved. This is called centralized unification. If

people still do not understand problems, if they have ideas but have not expressed them, or

are angry but still have not vented their anger, how can centralized unification be

established? If there is no democracy we cannot possibly summarize experience correctly.

If there is no democracy, if ideas are not coming from the masses, it is impossible to

establish a good line, good general and specific policies and methods. Everyone knows that

if a factory has no raw material it cannot do any processing. If the raw material is not

adequate in quantity and quality it cannot produce good finished products. Without

democracy, you have no understanding of what is happening down below; the situation will

be unclear, you will be unable to collect sufficient opinions from all sides; there can be

no communication between top and bottom; top-level organs of leadership will depend on

one-sided and incorrect material to decide issues, thus you will find it difficult to avoid

being subjectivist; it will be impossible to achieve true centralism.

“Our centralism is built on democratic

foundations; proletarian centralism is based on broad democratic foundations.”

—Mao, from a “Talk at an Enlarged

Central Work Conference”, in the section “The problem of democratic centralism”, January 30,

1962; Chairman Mao Talks to the People, Stuart Schram, ed., (NY: Pantheon, 1974), pp.

163-164.

CEO [Chief Executive Officer]

The top boss in charge of the day-to-day operations of a capitalist corporation. Although strictly

speaking CEO’s are subordinate to the Board of Directors of the corporation, in actual practice

they usually have quite a free hand. Moreover, they often also simultaneously hold the position of

Chairman of the Board as well as CEO, which really puts them almost completely in charge.

In capitalist theory corporations are owned and

supposedly controlled by those who own stock in that company, and the managers only “work for

those owners”. However, the CEO and other top managers of most corporations are in a position to

effectively loot a considerable part of the wealth of the companies they run and actually

do control. They do this through awarding themselves huge salaries, and via company stock sales to

themselves at huge discounts from market prices, etc. All capitalist corporations are in effect

gangs of capitalist thieves who exploit and steal the wealth created by their ordinary workers. But

within those gangs the top managers are the biggest thieves of all, and even steal disproportionate

amounts of the overall loot from the other share holders.

CEO’s in contemporary American capitalism are

typically paid vast amounts of money, including not only official salaries which are often in the

millions of dollars annually, but also with stock options, endless additional benefits, perquisites,

and so forth. And when they leave or retire—even if they get forced out because of gross

mismanagement of the corporation (a common occurrence)—they are usually presented with enormous

departure bonuses (often referred to as “golden parachutes”).

“Forty-four percent of U.S. CEOs have contracts that call for them to receive

severance payments even if they’re fired for committing fraud or embezzlement.”

—New York Times report, quoted in The Week, October 12, 2007, p. 40.

[American corporations today often “reward” their workers with small-scale

social events such as pizza parties, where the company graciously picks up the tab for a few

pizzas. —Ed.]

“If pizza parties are adequate reward

for hard work or extraordinary accomplishment, why aren’t they a bigger part of CEO

compensation?” —Disgruntled comment by someone using the handle “Gritty 20202” on the

Internet in 2023.

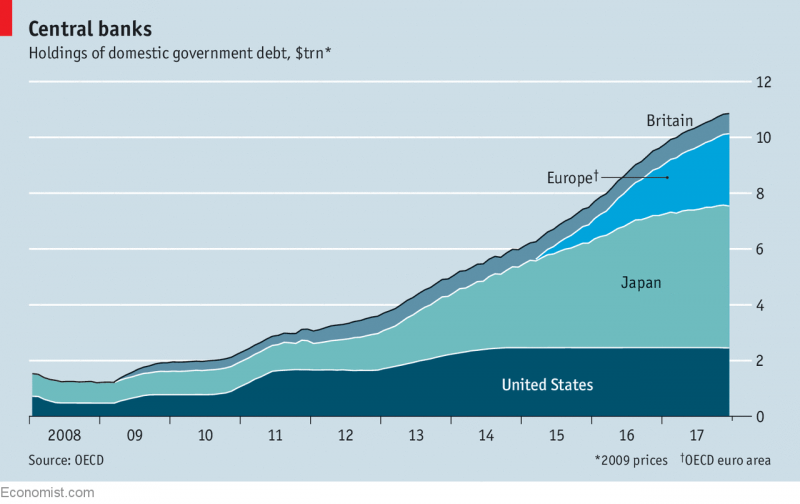

Central banks (see entry above) generally create new money in the economy in indirect ways. One

primary method they use to do so is through buying bonds which their government issues by simply

crediting a government bank account with that amount of money. The government may then spend that

money for any purpose. It is really equivalent to the government just printing money and spending

it, but supposedly this indirect method can keep the process under tighter control. The creation

of new money is therefore the same thing as increasing the formal amount of government debt which

the central bank holds.

Central banks (see entry above) generally create new money in the economy in indirect ways. One

primary method they use to do so is through buying bonds which their government issues by simply

crediting a government bank account with that amount of money. The government may then spend that

money for any purpose. It is really equivalent to the government just printing money and spending

it, but supposedly this indirect method can keep the process under tighter control. The creation

of new money is therefore the same thing as increasing the formal amount of government debt which

the central bank holds.