MATCHING SKILLS AND TASKS

In any collective endeavor the best results can be achieved if the various sub-tasks

to be done are assigned to, or are taken on by, the most appropriate people. That is to

say, it is important to match people’s skills as best we can to the tasks needing to be

done.

It is surprising how often this obvious

principle goes unappreciated by managers in capitalist corporations! Since most often

they are not workers themselves (and often never have been), bourgeois managers frequently

are ignorant of the specific skills that are required to accomplish some task, and are

often also ignorant of the different sets of skills that individual workers possess. Thus

they tend to view “their” workers as interchangeable parts.

Unfortunately, this tendency can also

exist within revolutionary parties, or at a socialist factory in a revolutionary society.

One of the many important reasons we need workers’ participation in management under

socialism is to avoid this problem. Similarly, this is one of the important reasons we

need to avoid commandism and arbitrary decision making,

without consultation among comrades, within the revolutionary movement.

“A worker-agitator who is at all gifted and ‘promising’ must not be

left to work eleven hours a day in a factory. We must arrange that he be maintained

by the Party; that he may go underground in good time; that he change the place of

his activity, if he is to enlarge his experience, widen his outlook, and be able to

hold out for at least a few years in the struggle against the gendarmes. As the

spontaneous rise of their movement becomes broader and deeper, the working-class

masses promote from their ranks not only an increasing number of talented agitators,

but also talented organizers, propagandists, and ‘practical workers’ in the best

sense of the term...” —Lenin, “What Is To Be Done?” (1902), chapter 4, section D,

LCW 5:472.

[As Lenin implies here, we must

seek out and further develop the skills of our comrades and of the masses, and help

them put those skills and capabilities to the best use in promoting the revolution!

—Ed.]

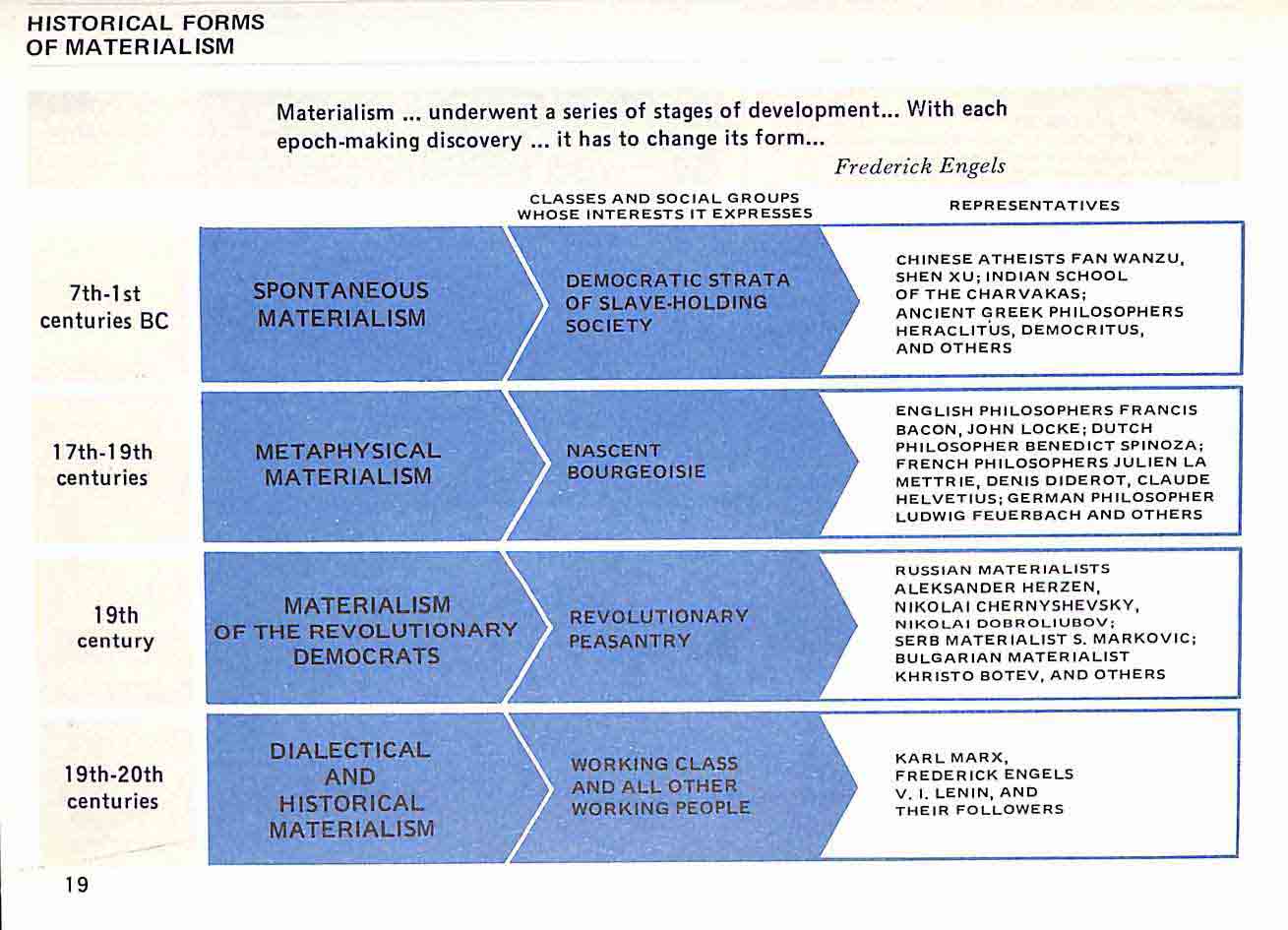

MATERIALISM — How Dialectical Materialism Developed Out of Mechanical Materialism

Dialectical materialism is the more sophisticated form of materialism which was created by Marx, Engels

and their followers. But what were the social and scientific developments in their day which led to the

creation of this more profound theory? The answer is brought out well in the following:

“The science of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had been mainly mechanistic.

That is to say, it had assumed that nature was rather like a machine, made of fixed parts which moved

and interacted according to unchangeable laws, continually repeating the same movements and producing

the same results. The great discoveries of the industrial revolution, on the other hand, were mostly

concerned with the transformations and processes of evolution and development which take place in

nature. As a result, the conception of nature was revolutionized. Instead of the same motions

endlessly repeated, there emerged the picture of one form of motion being transformed into another,

and of change, development and evolution taking place everywhere.

“Discoveries in thermodynamics, for example,

showed how different energies are transformed into one another—as in the steam engine heat is

transformed into mechanical motion. Faraday showed how electrical forces are generated by a moving

magnet. The investigation of living organisms showed how all forms of life are developed from cells.

The Darwinian theory showed how all living species had evolved by natural selection from more

primitive forms. Geology showed how the earth itself changed, and astronomy that the stars are not

unchanging....

“In this way the sciences began to present a

picture of the material world in which everything could be explained from the material world itself,

in terms of processes of the transformation and development of material systems. A living cell is a

chemical system, and the original forms of life themselves came into being by the formation of

complex molecules. Man himself evolved by natural selection from among the primates. It remained to

work out how human society and human consciousness could have evolved from natural rather than from

supernatural causes—and this was done by the hypothesis of historical materialism, put forward by

Marx at about the same time as Darwin was working out the theory of evolution by natural selection.

This was a hypothesis comparable with those advanced in other fields of fundamental theory in the

sciences....

“Adopting this strictly materialist standpoint,

Marx and Engels at the same time rejected the mechanistic assumptions of earlier materialist

philosophies. The world was to be understood, not as a complex of things, but as a complex of

processes, in which apparently stable things, together with their reflections in our consciousness,

go through an unending succession of coming into being and ceasing to be, of change and development.”

—Maurice Cornforth, Marxism and the Linguistic Philosophy (1967), pp. 58-59.

MATERIALISM VS. IDEALISM

This is the basic question, and the most fundamental dispute, in the entire history of

philosophy. Which is primary and which depends on the other: Matter or mind? For

us materialists, the answer is completely obvious: the material world exists independently of

anyone’s mental ideas and thoughts of it, and mind and mental phenomena are merely a set of

functional characteristics of certain complex organizations of matter (i.e., brains).

See also:

IDEALISM,

IDEALISM—Origin Of [Engels quote]

“The spirit of materialism is intolerable to the idealist!!” —a

wonderfully ironic statement by Lenin while speaking specifically of Hegel’s discussion

of Democritus, “Conspectus of Hegel’s Book Lectures

on the History of Philosophy” (1915), LCW 38:267.

“Teacher: Si Fu, name the basic questions of philosophy.

“Si Fu: Are things external

to us, self-sufficient, independent of us, or are things in us, dependent on us,

non-existent without us?

“Teacher: Which opinion is

the correct one?

“Si Fu: There has been no

decision about it....

“Teacher: Why does the

question remain unresolved?

“Si Fu: The Congress which

was to have made the decision took place two hundred years ago at Mi Sang monastery,

which lies on the bank of the Yellow River. The question was: Is the Yellow River real

or does it exist only in people’s heads? But during the Congress the snow thawed in the

mountains and swept away the Mi Sang monastery with all the participants in the Congress.

So the proof that things exist externally to us, self-sufficiently, independently of us

was not finished....”

—Bertolt Brecht, Turandot,

Scene 4A.

MATERIALISM AND EMPIRIO-CRITICISM [Book]

This is a great philosophical work by Lenin which defends and develops scientific

materialism. It was written in 1908 and first published in May 1909. Its purpose was to

combat various Kantian, religious and other

idealist doctrines which were becoming popular among a certain

strata of the Russian revolutionary movement, including among some of the Bolsheviks.

In the late 19th century, physics

entered into a period of crisis with the discovery of radioactivity and other anomalies, and

the advent of the earliest quantum-related speculations. Thus some of the materialist

assumptions, that most physicists had explicitly or tacitly assumed, came into question,

especially by scientists and philosophers who had been strongly influenced by Kant or early

forms of positivism. These idealist theories spread beyond

physics and philosophy, and led to a resurgence of subjective

idealism among intellectuals. It was the intrusion of this trend into the revolutionary

movement itself that alarmed Lenin, and moved him to write this book.

Since at the beginning of the 21st

century Kantianism and various other forms of philosophical idealism are once again quite

rampant, even among some philosophers who claim to be Marxists or influenced by Marxism, and

since these people are misleading many young revolutionaries in the universities, it is all

the more important to once again promote the serious study of Lenin’s Materialism and

Empirio-Criticism.

“The book is the outcome of a prodigious amount of creative scientific

research carried out by Lenin during nine months. His main work on the book was carried

out in Geneva libraries, but in order to obtain a detailed knowledge of the modern

literature of philosophy and natural science he went in May 1908 to London, where he

worked for about a month in the library of the British Museum. The list of sources

quoted or mentioned by Lenin in his book exceeds 200 titles.

“In December 1908 Lenin went from

Geneva to Paris where he worked until April 1909 on correcting the proofs of his book.

He had to agree to tone down some passages of the work so as not to give the tsarist

censorship an excuse for prohibiting its publication. It was published in Russia under

great difficulties. Lenin insisted on the speedy issue of the book, stressing that ‘not

only literary but also serious political obligations’ were involved in its publication.

“Lenin’s work Materialism and

Empirio-criticism played a decisive part in combating the Machist revision of Marxism.

It enabled the philosophical ideas of Marxism to spread widely among the mass of party

members and helped the party activists and progressive workers to master dialectical and

historical materialism.

“This classical work of Lenin’s

has achieved a wide circulation in many countries, and has been published in over 20

languages.” —Note 11, LCW 14 [1968].

“Of this book by Lenin, A. A. Zhdanov wrote that ‘every sentence is like

a piercing sword, annihilating an opponent.’ It is a devastating attack against modern

idealism, a brilliant defence of the materialist standpoint, and a development of the

basic ideas of dialectical materialism in the light of scientific discovery.

“It was written in 1908 in the

period following the defeat of the 1905-7 Revolution in Russia. The reader should consult

the History of the C.P.S.U.(B), Chapter IV, Section I, in order to understand the

background.

“It was a time of great difficulty

for the revolutionary working class movement in Russia. Reaction was making savage

attacks upon the working class, and with this went an ideological offensive against

Marxism, which fashionable writers represented as being exploded and ‘out of date.’ This

situation affected a group of the party intellectuals. They began to write books and

articles claiming to ‘improve’ Marxism and to ‘bring it up to date’ in the light of

‘modern science,’ but in reality attacking its entire theoretical foundations.

“Lenin’s Materialism and

Empirio-Criticism was written against this group. It safeguarded the theoretical

treasure of Marxism from the revisionists and renegades. But more than that, it

provided a new materialist generalization of everything important and essential acquired

by science, and especially the natural sciences, since Engels’ death.

“The reader unused to philosophical

literature will find an initial difficulty in understanding some of the terms used in

this book, and the references to various bourgeois philosophers and scientists. The term

‘Empirio-Criticism’ is used to denote a whole sect of modern idealists. Lenin shows that

their theories are copied from those of the Anglo-Irish philosopher,

George Berkeley (1684-1753), who taught that material

things have no real existence and that nothing exists but the sensations in our own minds;

from the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), who taught

that we can have no knowledge of ‘things-in-themselves,’ which are mysterious and

unknowable; and from the Austrian scientist and philosopher Ernst

Mach (1838-1916), who taught that bodies were nothing but ‘complexes of sensations.’

Lenin’s references to and quotations from these philosophers and their modern followers

are, however, sufficiently detailed for the reader who follows the argument attentively

to understand what it is all about, even without prior knowledge.

“In Materialism and

Empirio-Criticism is contained:

“1. A devastating exposure of the

idealism of the modern ‘philosophy of science’ which pretends that matter existing

outside us is an abstraction and that what ‘really’ exists consists of ‘complexes of

sensations.’

“Ridiculing the ‘scientific’

pretensions of this philosophy, Lenin asks:

“‘Did Nature exist prior to man?’

“‘Does Man think with the help of

the brain?’

“Science answers ‘Yes’ to both

questions; and that means that matter objectively exists independent of and prior to

human consciousness and sensation.

“2. The clear assertion and

explanation of the most important features of the materialist conception of nature, in

particular—

The practical test

of knowledge;

The relationship

of relative and absolute truth;

The absolute

existence of matter, as the objective reality given to man in his sensations;

The objective

validity of causality and causal laws;

The objectivity

of space and time, as forms of all being.

“3. The analysis of the crisis in

modern physics, which arises from the contradiction between new discoveries and the

mechanistic ideas of ‘classical’ physics. Lenin shows how two trends arise in physics,

a materialist and an idealist trend. He exposes the sham pretensions of the latter and

demonstrates that ‘modern physics is in travail; it is giving birth to dialectical

materialism.’

“4. The demonstration of the

partisan character of all philosophy, of the irreconcilability of the struggle

of materialism against idealism. Lenin shows that Marxism is materialism, irreconcilably

opposed to every form of idealism and of attempted compromise between materialism and

idealism.” —Maurice Cornforth, Readers’ Guide to the Marxist Classics (1952),

pp. 27-28.

MATHEMATICAL OBJECT (or ENTITY)

This category includes the various kinds of numbers (natural numbers such as 1, 2, 3...),

integers, real numbers (i.e., numbers that can be represented as a ratio or fraction of

two integers), complex numbers, vectors, etc., and the various types of geometric

shapes (points, lines, planes, triangles, circles, pentagons, cubes, spheres, etc.), and so

forth. All of these kinds of entities are abstractions;

that is, they are concepts or ideal figures that have been abstracted out of objects or

collections that approximate them in some way in the physical world.

From pairs of things we have abstracted the

concept of the number 2; from trios we have abstracted the number 3; from very tiny specks and

motes we have abstracted the concept of a mathematical point; from things in a row or more or

less straight scratches and marks we have abstracted the concept of a straight line. Once a

stock of such elementary abstractions have been formed we can extend them and combine them.

Thus the number 31 can be comprehended even if we have never directly abstracted that

particular number from varying collections of 31 items. A regular equilateral 73-sided

two-dimensional figure can be contemplated (and recognized to approximate a circle) even if we

have never actually seen a close physical approximation of such a figure.

In the philosophy of mathematics there have

been many and continuing disputes about the actual (“ontological”)

nature of mathematical objects, along with disputes about the nature of abstractions in general.

In what sense can these entities be said to “exist”? Do they form part of “reality”, even

though they are not physical things? Such questions arise because people were (and often still

are) very confused by the nature of abstraction. As usual in philosophy, the two big camps

are materialism and idealism.

Mathematical idealism is often termed mathematical Platonism (see entry below).

We materialists view abstraction as being an

important and necessary way for human beings to think about and understand the world, meaning

primarily the physical world and human society. Our ability to form abstractions evolved in

our species (and to lesser degrees in other animal species on Earth) because this promoted

our survival. But we grant that some of the systems of abstractions we have created are so

complex, and the interrelationships among the different abstract elements are sometimes so

difficult to immediately grasp, that the thorough investigation of these abstract realms

often requires a tremendous amount of concentrated thought. This is especially the case in

mathematics. This is the “world of abstractions” that mathematicians (and others) often

imagine to be on an ontological par with the physical world.

There are indeed actual logical relationships

between mathematical objects, relationships which are not themselves arbitrary or

“mere human inventions”, but real relationships that derive from the definitions and logical

structure of those systems of abstract mathematical objects. On the one hand, humans did

create these abstract mathematical objects in their minds, but the mathematical objects they

created have objective characteristics. Other intelligent life somewhere in the universe,

which creates those same abstract mathematical objects, will come to the same mathematical

conclusions about them as we do—because the same logical relationships will hold between

those same abstract elements. We find that the sum of the interior angles of a two-dimensional

Euclidean triangle add up to 180 degrees, and so will they.

The branches of mathematics that we human

beings have created are not themselves “part” of the universe (except in the sense that the

representations of this mathematics, whether on paper or in our brains, has a physical

basis). If you list all the things that exist in the universe, the number 2 will not be

among them along with trees and chairs. But on the other hand, the systems of mathematical

abstraction do have objective logical relationships within them. The thorough exploration of

those objective logical relationships between these abstract mathematical “objects” is what

mathematics is all about.

MATHEMATICAL PLATONISM

One of a number of related views about the nature of mathematical

“objects” (such as numbers, points, lines, and triangles) and their properties and

inter-relationships, which are (or seem to be) along the lines of Platonism

in general. That is, ideas about mathematical abstractions which are examples of philosophical

idealism.

Platonists are philosophical idealists, who

hold that ideas (rather than matter) are primary in the world. Since mathematics is the

exploration of the logical interrelationships between certain sorts of abstractions (relating

primarily to quantity and form), and since abstractions are themselves ideas, mathematicians

have very often been seduced by Platonism. They often view abstract entities such as numbers

and geometric shapes as having an independent existence from the physical world (in addition

to physical objects). For example, the great British number theorist G. H. Hardy wrote:

“For me, and I suppose for most mathematicians, there is another

reality [besides ‘physical reality’ —SH], which I will call ‘mathematical reality’....

I believe that mathematical reality lies outside us, that our function is to discover or

observe it.” —G. H. Hardy, A Mathematician’s Apology (Cambridge University

Press, 1969), p. 123.]

Martin Gardner, the expert on mathematical games, put it this way in explaining why he is

an “unashamed Platonist” when it comes to mathematics:

“If all sentient beings in the universe disappeared, there would remain

a sense in which mathematical objects and theorems would continue to exist even though

there would be no one around to write or talk about them. Huge prime numbers would

continue to be prime even if no one had proved them prime.” —Martin Gardner, When You

Were a Tadpole and I Was a Fish (2009)]

The idealist flaw in the thinking here is that while prime numbers will still be prime

(whether or not anyone has yet proven this for particular numbers), numbers are

nevertheless not part of the world in the sense that atoms and planets and people are.

Numbers are intellectual abstractions, or mental constructs. And whether a number is prime

or not is a matter of a certain type of logical relationship of that number to the other

numbers.

The “worldly existence” of ideas,

abstractions, and indeed even numbers and geometric shapes, depends on the prior existence

of matter, if only in the form of thinkers who can generate such abstractions in their

mind/brain.

MATHEMATICS — and the World

The best and also most concise summary of the relationship of mathematics to the world is

that by Engels, appended below. Certainly all the primary mathematical conceptions, of

numbers, varying quantities, rates of change, various shapes and their relationships

(lines, triangles, circles, etc.) have been derived as abstractions from physical things and

processes in the world around us. It is true of course that these abstractions then allow us

to generate further abstractions of similar kinds. For example, while we have abstracted 3,

4 and 5-sided plain figures from things in the real world, probably no one has abstracted

137-sided figures from the actual world. Instead, we generalize and expand on our initial

abstractions, and create new abstractions in that way.

Mathematics, as an intellectual subject,

then becomes largely a matter of thinking about, and discovering, the logical relationships

between these various abstractions. Thus it has been proven that the sum of the interior

angles of a triangle in Euclidean two-dimensional space is always 180°. Is this something

that is true “of the world”? Actually, no! It is something that must be logically true, given

the definitions of the abstractions we have derived from the world. The physical world

itself (or parts of it) may, or may not, actually even exist in Euclidean space. Even the

surface of the earth, being on a sphere, which we are often concerned with, is not in fact a

two-dimensional Euclidean plane though it appears to be so very locally. And for that

reason we can apply the mathematics of a Euclidean plane to help us measure fields, use

the Pythagorean Theorem to successfully build houses with square corners and vertical

walls, and so forth.

Engels, in the quote mentioned, refers

to mathematics as one of the sciences. Is that really true? Well, it depends on how you

define the term “science”. If a science is defined as one of the areas of the investigation

of physical or social reality, then no, mathematics is not a science in that sense—even

though it is tremendously useful and even indispensable as a tool in virtually all the

actual sciences. Mathematics, as an independent subject, is instead the realm where the

logical relationships between many special abstractions from the world related to numbers,

shapes, and certain abstract processes, is at least largely independently investigated

separately from the further investigations of the physical world itself. At least this is

the case for what is called “pure” mathematics. What is known as “applied” mathematics is

often more of a combination of the development of mathematical theory together with

the further theorization about the nature of aspects of the physical world (and hopefully

based on actual investigations of the physical world). —S.H. [May 24, 2023.]

See also:

MATHEMATICAL LAWS

“Profound study of nature is the most fertile source of mathematical

discoveries.” —Joseph Fourier (1768-1830), The Analytic Theory of Heat (1822).

“Mathematicians are only dealing with the structure of reasoning,

and they do not really care what they are talking about. They do not even need to

know what they are talking about.... But the physicist has meaning to all his

phrases.... In physics, you have to have an understanding of the connection of words

to the real world.” —Richard Feynman, The Character of Physical Law.

[Although there is some truth

to these claims about mathematics, especially with regard to the ever more abstract

forms of modern mathematics, in the quote below Engels reminds us that mathematics

itself at least got its start in the form of abstractions from the real world. —Ed.]

“But it is not at all true that in pure mathematics the mind deals

only with its own creations and imaginations. The concepts of number and figure have

not been derived from any source other than the world of reality. The ten fingers on

which men learnt to count, that is, to perform the first arithmetical operation, are

anything but a free creation of the mind. Counting requires not only objects that can

be counted, but also the ability to exclude all properties of the objects considered

except their number—and this ability is the product of a long historical development

based on experience.... Like all other sciences, mathematics arose out of the

needs of men: from the measurement of land and the content of vessels, from

the computation of time and from mechanics. But, as in every department of thought,

at a certain stage of development the laws, which were abstracted from the real

world, become divorced from the real world, and are set up against it as something

independent, as laws coming from outside, to which the world has to conform. That is

how things happened in society and in the state, and in this way, and not otherwise,

pure mathematics was subsequently applied to the world, although it is

borrowed from this same world and represents only one part of its forms of

interconnection—and it is only just because of this that it can be applied

at all.” —Engels, Anti-Dühring (1878), MECW 25:37.

MATTER

1. [In dialectical-materialist philosophy:] All

the physical constituents of reality, including matter in the physics sense (see below) and

also energy. But this category does not include mind and mental

phenomena, which are special ways of looking at the functioning of certain complex

organizations of matter (e.g., brains).

“[T]he sole ‘property’ of matter with whose recognition

philosophical materialism is bound up is the property of being an objective

reality, of existing outside the mind.” —Lenin, Materialism and Empirio-Criticism

(1908), LCW 14:260-1.

“The history of philosophy and natural science provides an abundance of

material on the struggle between the materialist and idealist views of the world, between

the metaphysical and dialectical approaches to the phenomena of the world. This struggle

was connected above all with different ideas on the nature of matter....

“The atomistic ideas of Democritus

held sway over pre-Marxist materialist philosophers and the most important naturalists

down to the end of the 19th century. The thinkers of the past, following Leucippus and

Democritus, considered atoms to be indivisible, structureless and unchanging particles,

the ultimate ‘building blocks’ out of which all material objects are fashioned. In Newton’s

mechanics, a special role was played by a constant magnitude, mass, which Newton viewed

as a measure of the quantity of matter. Later philosophers and physicists equated it with

matter.

“Most pre-Marxist materialists did

not link the concept of matter with a materialist treatment of the basic question of

philosophy, i.e., the question of which is primary: matter or consciousness. The category

‘matter’ was often related not to the category ‘consciousness’, but to the categories

‘form’, ‘property’ and ‘motion’. The development of the natural sciences in the 17th and

18th centuries (mechanics, physics, biology, chemistry, etc.) prompted development based

on a notion of the primary basis (substance), the atomic structure of substance and the

crucial significance of mass, which began to be viewed as the fundamental attribute of

matter.

“This idea was expressed succinctly

in the 19th century by the well-known Russian scientist D. I. Mendeleyev, who wrote:

‘Substance or matter is that which, filling space, has weight, i.e., is a mass...—that

which makes up the bodies of nature and with which the movement and phenomena

of nature are performed.’ [The Foundations of Chemistry (1889), p. 1, in Russian.]

The materialists of the 18th century, and Feuerbach in the 19th century, made important

progress toward shaping a concept of matter, opposing matter to spirit, but only Engels

gave a consistent materialist answer to the fundamental question of philosophy. The

doctrine on matter was further developed in Lenin’s writings.

“In its most general form, as Lenin

showed, matter can be defined only by explicating its relationship to men’s consciousness.

In fact, in their variegated activity men come up against two incontestable facts: first,

that they exist in a specific milieu, in specific conditions—in nature, in society; and

second, that they think, that they have their own spiritual [or mental —ed.] world. Hence

the question, basic for every philosophical doctrine, of the relationship of thinking to

being, of spirit [mind] to nature. Materialist philosophy answers this question as follows:

there is an objective reality that exists independent of man and humanity—matter, which

is primary, human counsciousness being secondary.

“The consciousness of men and the

embryonic consciousness of animals is a property of highly organized matter; therefore,

consciousness cannot exist without matter, while matter existed before the emergence of

man and his consciousness. Consciousness is in effect the reflection of the material world

in the human brain.

“On the basis of the materialist

treatment of the fundamental question of philosophy, Lenin formulated the following most

general definition of the concept of matter: ‘Matter is a philosophical category denoting

the objective reality which is given to man by his sensations, and which is copied,

photographed and reflected by our sensations, while existing independently of them.’

[Lenin, Materialism and Empirio-Criticism (1908), LCW 14:130.]

“Lenin’s definition of matter focuses

attention on the universal, absolute property of matter, a property that belongs to matter

in all its guises, both the known and those yet unknown: its property of being objective

reality, of existing external to and independent of consciousness of whatever sort.”

—V. S. Gott, a Soviet philosopher

of science, This Amazing, Amazing, Amazing but Knowable Universe (Moscow: Progress,

1977), pp. 41-44.

2. [In contemporary physics:] The substance from which physical objects are composed; the

material substance that is generally considered to occupy space, have mass (“weight”), and

which most prominently exists in the form of atoms and their

constituent parts (protons, neutrons

and electrons). Matter in this sense is now known to be

interconvertible with energy, and this is one reason why there needs to be the broader

philosophical sense of the term ‘matter’ as well. Within contemporary physics there are

several categories of matter, including ordinary matter (of which everyday objects are

composed), anti-matter, and the hypothesized dark

matter.

See also:

“IMMATERIAL OBJECT”

Dictionary Home Page and Letter Index

MASSLINE.ORG Home Page

Materialism holds that there is a real objective world which exists independently of any mental

conception of it. Although this may seem like simple common sense to most of the readers of this

dictionary, this materialist conception had to develop over centuries of struggle against

idealist conceptions and philosophies which maintained that ideas

form the foundation of all reality.

Materialism holds that there is a real objective world which exists independently of any mental

conception of it. Although this may seem like simple common sense to most of the readers of this

dictionary, this materialist conception had to develop over centuries of struggle against

idealist conceptions and philosophies which maintained that ideas

form the foundation of all reality.![Length of required maternity leave in countries around the world. [Mother Jones, 2011.]](Photos/M/MaternityLeave-MJ-2011.jpg)