LABOR ARISTOCRACY

This is the very best-paid and privileged stratum of the proletariat, which has arisen mostly

within imperialist countries in the last century and a half. These are most often skilled

workers, whose special training gives them greater bargaining power with the capitalists with

regard to wages and benefits, especially where they are organized into strong craft unions.

In the richest imperialist countries, such as the U.S., some workers in the labor aristocracy

may even acquire some significant investments, such as rental property, stocks and bonds,

though the dominant part of their income is still from wages. (Only a very few people from

this stratum will actually break out of the working class entirely, even during boom

periods.)

However, it is still only possible for this

labor aristocracy to be as large as it is, and to receive as high wages and benefits as it

does along with acquiring some savings and investments in some cases, because of the

exploitation of large parts of the world by the imperialist ruling class. That international

exploitation leads to constant imperialist wars, and it is necessary for the ruling class to

pacify at least a major section of its workers at home with some small part of the wealth it

rips off from foreign countries (and from the “Third World” in particular).

The labor aristocracy, in turn, tends to

strongly support the bourgeoisie politically, and has in general an extremely low level of

proletarian class consciousness. In effect, this section of the working class has made an

accommodation with the capitalist-imperialists.

But in periods of serious economic crisis,

such as the U.S. and most of world capitalism are now in once again, the bourgeoisie is

finding it necessary to take back more and more of the higher wages and benefits it once could

easily afford to grant to a part of the working class. This is having the effect of reducing

the size of the labor aristocracy in the U.S. and most countries (though it is still growing

rapidly in one country—China). As the world capitalist crisis develops further, much of the

embourgeoised labor aristocracy will be once again driven down and reproletarianized.

“... the English proletariat is actually becoming more and more bourgeois,

so that the ultimate aim of this most bourgeois of all nations would appear to be the

possession, alongside the bourgeoisie, of a bourgeois aristocracy and a bourgeois

proletariat. In the case of a nation which exploits the entire world this is, of course,

justified to some extent.” —Engels, Letter to Marx, Oct. 7, 1858, MECW 40:343, online at:

http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1858/letters/58_10_07.htm.

“This aristocracy of labor, which at that time earned tolerably good

wages, boxed itself up in narrow self-interest craft unions, and isolated itself from the

mass of the proletariat, while in politics it supported the liberal bourgeoisie.” —Lenin,

“Harry Quelch”, Sept. 12, 1913, LCW 19:370, online at:

http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1913/sep/12.htm. [Lenin is speaking of

Britain, specifically.]

“But it would be dogmatic and wrong to believe that the labor aristocracy

always sides with the bourgeoisie. Historical events have demonstrated that it is not only

economic conditions which determine the political behavior of workers. Workers are able

to suffer adverse conditions for a very long time, in fact they even get used to them.

Dissatisfaction is caused primarily by a worsening of conditions, especially by a

rapid worsening. The same also applies to the labor aristocracy. It holds the side of the

bourgeoisie so long as its economic privileges are stable, but, if its position sharply

deteriorates, it may become an active participant in the revolutionary struggle. This

happened in Hungary in 1918-19 before the establishment of the dictatorship of the

proletariat when a sharp inflation plunged down the living standard of the workers.

Skilled workers who were receiving the highest rates reacted far more vehemently to the

worsening of their position than did badly paid workers. They joined the Communist Party

and often played a leading role in the fight to overthrow the bourgeoisie. Similar

developments were observed in the workers’ revolutionary movement in Germany.” —Eugen

Varga, Politico-Economic Problems of Capitalism (1968), p. 127.

[While what Varga says here may be

true in exceptional circumstances, there is also the possibility in modern society that

an outraged labor aristocracy, which suddenly comes under economic attack because of a

severe capitalist crisis, may also turn in its ideological confusion to support a fascist

movement (along with a major section of the petty-bourgeoisie). Moreover, even the

possibility of a section of the labor aristocracy under attack joining the revolutionary

movement depends on there being a serious and active revolutionary movement in the

first place, which can only be built up from nothing by focusing primarily on the lower

strata of the working class. —S.H.]

LABOR POWER

“By labor-power or capacity for labor is to be understood the aggregate of those

mental and physical capabilities existing in a human being, which he exercises

whenever he produces a use-value of any description.” —Marx, Capital, vol. I,

ch. 6: (International, p. 167; Penguin, p. 270.) “A commodity which its possessor, the

wage-worker, sells to capital.” —Marx, “Wage Labor and Capital”, (MECW 9:202, as edited

in Engels’s 1891 edition.)

Labor power is therefore the worker’s

ability to work, which is what is sold to the capitalist for the wages received.

Labor power is not the same as labor itself, however! As everyone is aware,

once the capitalists sell the products that the workers produce, and even after paying

the workers their wages (which means the market value of their labor power), they

still have a large surplus left over from which they take their profits. The

fact that the actual labor of the workers generates this additional

surplus value beyond the workers’ wages (i.e., beyond

the value of their labor power) means that the real implicit value of their actual

labor must greatly exceed the value of what they sell to the capitalists, their

labor power. And therefore labor power and labor must be carefully distinguished

if we are to understand the source of the capitalists’ profits.

The distinction between labor power and

labor is often confusing for those new to Marxist political economy. In addition to

Chapter 6

of Volume I of Marx’s Capital, another good place to go to clear up this confusion

is to carefully read Engels’s 1891 edition of Marx’s pamphlet, “Wage Labor and Capital”

and especially Engels’s introduction where he goes into the difference between labor power

and labor quite thoroughly. This edition is available in an inexpensive paperback from

International Publishers, and available online at

http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/wage-labour/index.htm.

Engels’s introduction is also available separately in MECW 27:194-201.

LABOR THEORY OF VALUE (LTV)

The fundamental theory in political economy, put forth by Marx, that the economic

value of any commodity

in a capitalist system of production is proportional to the average

socially necessary labor time that it

takes to produce that commodity. Thus if the average labor time necessary to produce a

certain type of overcoat is 25 times as great as the average labor time it takes to produce

a loaf of bread, the coat will have a value 25 times as great as that of the loaf. Marx,

however, understands full well that the actual prices of that

type of coat and that sort of loaf of bread might vary somewhat from this ratio for a

variety of reasons. But the analytical foundation, and most basic explanation for the

difference in the prices of the two commodities will still lie in the different quantities

of labor time necessary to make each.

Classical political economy also agreed

with this theory (in Ricardo, for example), at least in rough

outlines. But modern bourgeois economists reject it because they are loath to admit that

the working class, working on the products of nature, produces all value. They try instead

to explain value in terms of marginal supply and

demand, and so forth. But this leaves the usual fairly uniform differences in value

between the coat and the loaf of bread as quite mysterious. Alternately, they attempt to

explain the differences in value in terms of differing prices of production, but this begs

the question since they cannot supply any independent explanation for why prices of

production themselves differ!

All Marxists, or at least all those who

we care to consider as genuine Marxists in the sphere of political economy, agree with

the basic labor theory of value as briefly outline above. However, there are some secondary

aspects of the precise theory of value as put forward by Marx, about which even Marxists

can disagree. Marx, for example, said that only human labor, and only human labor

employed in the current production process, can create new

(surplus) value. Thus Marx does not seem to allow for the production of surplus value

by non-humans under any circumstances whatsoever. (See:

ANDROID THOUGHT EXPERIMENT ) Moreover,

Marx claimed that if a worker makes a machine and then uses that machine to produce

some commodity, only the labor time spent using the machine contributes to the

surplus value generated in the final commodity. An alternate view (which I for one hold)

is that the machine also allows the worker using it to continually reuse the labor

which went into making the machine, and therefore that both the new labor and the

re-used older labor will contribute to surplus value being generated in the final commodity.

For more on this, see the entry below. —S.H.

LABOR THEORY OF VALUE — Revised Form

This is a modified version of the labor theory of value (LTV) from that put forward by Marx.

It agrees with the fundamental proposition that the value

of a commodity produced in a capitalist system of production is solely due to the average

socially necessary labor time required

to produce that commodity. But it disagrees with Marx in that it views machinery as a way

of reusing the time spent in past labor (making the machine), and hence as also contributing

to surplus value along with the current labor time

expended. Here is the argument for making this modification:

“1) There is nothing mysterious nor magical about human labor

that can make it alone capable of generating surplus value in a system of

capitalist production. (Marx never adequately explained just why only human

beings supposedly have this capability, and thus left it all very mysterious.

He did say that human labor differs from animal efforts in that it is

conscious and purposeful, but

he did not explain why that makes any difference in this regard.) There must

be a good answer to the question, ‘Why is human labor able to produce surplus

value?’ It is incumbent on Marxist political economy to state precisely what the

answer to this question is.

“2) Furthermore, it is not

human creativity or intelligence that explains why human labor can generate surplus

value. (Some labor that generates surplus value requires very little

intelligence and shows virtually no creativity, such as certain types of extremely

repetitive assembly line work. And, on the other hand, some machinery already

demonstrates considerable intelligence and sometimes even some creativity—though

artificial creativity is much rarer so far, and is mostly confined to software, such

as certain expert systems.)

“3) Moreover, there is

no single specific human capability which, when exercised, alone is

able to generate surplus value. (On the contrary, there is an indefinitely large

number of actual things human workers can do which can generate surplus value, and

new ones are constantly being developed as production processes change.)

“4) Moreover, even now a

great many of these specific things which humans can do, and which generate surplus

value, can also be done by machines. (And in historical terms, machines are being

rapidly improved in the abilities to replace human beings in more and more types of

work.)

“5) All the sorts of

things that human beings can do which create surplus value come in degrees, from

very crude and primitive efforts to the highly skilled and sophisticated. This is

why we first see machines replacing the cruder forms of human labor, and then—as

the machines are improved—ever more sophisticated forms of human labor of the same

type.

“6) The thing that really

explains why human beings are able to generate surplus value is simply that human

beings can be ‘used over and over’ in the capitalist production process. (I.e., they

are not used up in the production of any commodity, as raw materials are.)

“7) But if the last principle

is true, then anything else that is used in the production process, without

being used up in each output commodity (i.e., tools and machinery), should also

contribute to surplus value.

“8) However, machines and

tools themselves were created by past human labor, and in fact all commodities that

presently exist are in the final analysis the result of the application of direct

or indirect human labor in various forms to the natural products of the world

around us.

“9) It is in general

impossible to quantitatively compare goods (or commodities) by comparing their

use values, since use values are so diverse, tend to

be unrelated to each other, and depend on the diverse and ever changing needs and

subjective desires of different individuals. (Whether a loaf of bread or a warm

coat is of greater use value to a person depends on the situation.)

“10) But there is an

underlying basis, and only one such feasible basis, for quantifying the differences

in exchange values for different commodities: the socially necessary labor

times incorporated into them. (So far this means just human labor, though

if androids are ever constructed, or if sentient aliens were to show up on earth

and also become workers, it would then include their labor.) Moreover, the labor

considered here must include not only the direct labor, but also the

properly apportioned indirect, or past labor contributed both in

the form of raw materials and tools & machinery. (The actual exchange values we

see, however, may be adjusted from this total socially necessary labor time for

various reasons, but the underlying labor time still forms the primary basis for

these exchange values.)

“11) Thus the labor theory

of value (LTV) remains essential in political economy. (Systems, like Sraffa’s,

that derive output prices directly from input quantities and prices (including

labor-power prices) may be technically possible, but are irrelevant here.

Political economy needs to explain a lot more than one price in terms of others.

For example it needs to explain how exploitation occurs and the deep reasons for

capitalist economic crises. (Furthermore, all prices themselves implicitly

relate to socially necessary labor times; the fact that a car costs $20,000 is

meaningless except within the framework where workers are paid definite amounts

for an hour of their labor time.) Sraffaian economics obscures such things. We

need to stay true to a profoundly political economics, a political economy

that clearly exposes the genuine human relationships at the bottom of

things.)

“12) But Marx’s specific

version of the LTV needs to be modified in one major way: It is not only

current labor which produces surplus value in a system of capitalist

production, but also the continuing use of past labor (embodied in tools

and machines). Modifying the LTV in this way allows us to resolve otherwise

insurmountable logical and conceptual problems in traditional Marxist political

economy. This revised LTV is far more coherent and defensible, but retains the

essential aspects of the traditional Marxist explanations for exploitation, the

source of capitalist profits, the underlying source of capitalist overproduction

crises as arising from the exploitation of labor in the capitalist production

process itself, and so forth.” —Scott Harrison, adapted from “Letter to Frank S.

about the labor theory of value” (Dec. 8, 2003), online at:

http://www.massline.org/PolitEcon/ScottH/Let_LTV.htm

LABOR UNIONS: U. S. — Long-term Decline Of

For many decades the size and strength of U.S. labor unions has been in a long-term decline.

Union membership, as a percentage of the labor force, has declined tremendously. As of 2012

the percentage of American workers in unions fell to 11.3%, the lowest since 1916 when it

was 11.2%. In private industry the figures were even worse: the percentage of unionized

workers was only 6.6%.

American trade unionism since the 1930s, at

least, has been virtually entirely a reformist movement, attempting to improve the lot of

workers economically but within the capitalist system. In no way was it a

revolutionary movement working toward the overthrow of capitalism. It made some economic

advances for a while, but as it became more and more bourgeois it also became less and less

militant. It members failed to comprehend that the gains in wages and benefits won through

unions, like all reformist gains under capitalism, are never secure and permanent. Eventually

the ruling class will succeed in striping away those gains and driving the workers down

again, especially when the developing economic crisis of its own capitalist system forces

it to do so.

LABOR’S SHARE OF PRODUCTION (In the U.S.)

![Index comparing labor’s share of income in the U.S. from year to year. [Federal Reserve data.]](Photos/L/IndexLaborShareIncome-2011-10.png) Since labor, applied to the resources of nature, is responsible for the production of

all wealth, by rights “labor’s share” of what is produced should be 100%.

But not only does the very tiny capitalist class take a very large percentage of what

is produced in the U.S. every year, over time they have been taking an ever-greater

percentage of it. Considering all the goods and services produced in the country (i.e.,

Gross Domestic Product), in 1974 the millions of employees of

all kinds added together received just 59% of the total. By 2009, that had fallen to

just 55%. In other words, the working class, which makes up over 90% of the population,

barely receives half of what it produces. And actually the situation is much worse even

than that, since these figures are grossly exaggerated. For example, many capitalists,

including even the CEO’s of giant corporations, are themselves counted as “employees”!

It is likely that the real situation is that the working class, even in this extremely

wealthy country, receives considerably less than half of what it produces each year.

Moreover, these figures are for gross income. After the government extracts all its many

taxes (much of which goes for imperialist wars and other things which benefit the rich

rather than the poor), the fraction of the wealth produced by the workers that they

actually are allowed to keep is even further reduced! And low as this percentage

now is, over time it is getting ever smaller. [The statistics here come from the

“Economics Scene” column, by David R. Francis, The Christian Science Monitor,

Feb. 21, 2010, p. 23.]

Since labor, applied to the resources of nature, is responsible for the production of

all wealth, by rights “labor’s share” of what is produced should be 100%.

But not only does the very tiny capitalist class take a very large percentage of what

is produced in the U.S. every year, over time they have been taking an ever-greater

percentage of it. Considering all the goods and services produced in the country (i.e.,

Gross Domestic Product), in 1974 the millions of employees of

all kinds added together received just 59% of the total. By 2009, that had fallen to

just 55%. In other words, the working class, which makes up over 90% of the population,

barely receives half of what it produces. And actually the situation is much worse even

than that, since these figures are grossly exaggerated. For example, many capitalists,

including even the CEO’s of giant corporations, are themselves counted as “employees”!

It is likely that the real situation is that the working class, even in this extremely

wealthy country, receives considerably less than half of what it produces each year.

Moreover, these figures are for gross income. After the government extracts all its many

taxes (much of which goes for imperialist wars and other things which benefit the rich

rather than the poor), the fraction of the wealth produced by the workers that they

actually are allowed to keep is even further reduced! And low as this percentage

now is, over time it is getting ever smaller. [The statistics here come from the

“Economics Scene” column, by David R. Francis, The Christian Science Monitor,

Feb. 21, 2010, p. 23.]

The chart at the above right (from the St.

Louis branch of the Federal Reserve) shows an index value comparing the share of national

income received by labor from year to year (with 2005 being arbitrarily set to 100). As

is evident, labor’s share of income is sinking like a rock, and is now at historic lows.

LAISSEZ-FAIRE [Pronounced: lassay fair]

[From the French, meaning “to let people do as they please”.] The bourgeois doctrine

which opposes any governmental interference in the economy beyond that necessary to

maintain peace and sacred capitalist property rights. This was well-nigh universally

accepted by bourgeois economists in the 19th century, especially after

John Stuart Mill popularized it in his Principles

of Political Economy in 1848. However, during the imperialist era, and especially

during the Great Depression of the 1930s, much of

the bourgeoisie and many of its apologists came to appreciate that much government

intervention in the economy on behalf of the capitalists was highly desirable, and

even necessary for the continuation of capitalism. In particular

Keynesian economists argued that the capitalist economy had

to be carefully “managed”, and even the more traditional economists of the

“neo-classical synthesis” school all

recognized that the government at least needed to manage interest rates, the money supply,

and so forth. After the stablization of capitalism for a long period after World War II,

laissez-faire (in a somewhat less pure form) came back into fashion again, often under

the new name (for much the same old ideas), neo-liberalism.

It is really only with the financial crash of 2008 and the deepening crisis leading toward

the development of a new depression that bourgeois economists are once again

starting to question their doctrine of near total faith in the virtues of laissez-faire

and the “free market”.

LAO ZI [also Romanized as Lao Tzu and Lao-Tse]

(6th century BCE)

Chinese philosopher and sage, the original source of Taoism.

Lao Zi (which literally means “the old master”) inspired the semi-religious Taoist book

Tao-te-Ching (“The Way of Power”) which was compiled some 300 years after his

death, and which teaches self-sufficiency, simplicity and detachment. From the Marxist

standpoint, Lao Zi is of interest mostly because of the primitive, but intriguing,

dialectics that he put forward, and also his faith in the people. For example, consider

this fine statement attributed to him, which sounds very much like the Maoist

mass line:

“Go to the people.

Live with them.

Learn from them...

Start with what they know;

Build with what they have.

But with the best leaders,

When the work is done,

The task accomplished,

The people will say,

We have done this ourselves!”

LASSALLE, Ferdinand (1825-1864)

German journalist, lawyer, and petty-bourgeois socialist.

“Lassalle was a German petty-bourgeois socialist who played an

active part in organizing (in 1863) the General Association of German Workers, a

political organization that existed up to 1875. The programmatic demands of the

Association were formulated by Lassalle in a number of articles and speeches.

Lassalle regarded the state as a supra-class organization and, in conformity with

that philosophically idealist view, believed that the Prussian state could be

utilized to solve the social problem through the setting up of producers’

co-operatives with its aid. Marx said that Lassalle advocated a ‘Royal-Prussian

state socialism’. Lassalle directed the workers towards peaceful, parliamentary

forms of struggle, believing that the introduction of universal suffrage would

make Prussia a ‘free people’s state’. To obtain universal suffrage he promised

Bismarck the support of his Association against the liberal opposition and also

in the implementation of Bismarck’s plan to reunite Germany ‘from above’ under

the hegemony of Prussia. Lassalle repudiated the revolutionary class struggle,

denied the importance of trade unions and of strike action, ignored the

international tasks of the working class, and infected the German workers with

nationalist ideas. His contemptuous attitude towards the peasantry, which he

regarded as a reactionary force, did much damage to the German working-class

movement. Marx and Engels fought his harmful utopian dogmatism and his reformist

views. Their criticism helped free the German workers from the influence of

Lassallean opportunism.” —Note 140 to LCW vol. 5, pp. 558-559.

LATHI [Pronounced: lah-tee, or lah-thee (to

rhyme with catty or Cathy)]

[From Hindi and related languages:] A stick or cane, typically 3 or 4 feet long, used

in a type of martial arts in India (often with longer sticks), but more commonly today

known because of its use by police forces to force submission by the masses. Lathis

are typically made of wood or very strong cane and often have a sturdy metal cap on the

end. Blows from them can cause serious injury and sometimes even death. Britain, when

it controlled India as a colony, first introduced lathis as a police weapon. They also

developed what is known as the lathi charge (or sometimes as one word,

lathicharge), where rows of police charge the protesting masses in military

fashion and viciously beat them.

[From Hindi and related languages:] A stick or cane, typically 3 or 4 feet long, used

in a type of martial arts in India (often with longer sticks), but more commonly today

known because of its use by police forces to force submission by the masses. Lathis

are typically made of wood or very strong cane and often have a sturdy metal cap on the

end. Blows from them can cause serious injury and sometimes even death. Britain, when

it controlled India as a colony, first introduced lathis as a police weapon. They also

developed what is known as the lathi charge (or sometimes as one word,

lathicharge), where rows of police charge the protesting masses in military

fashion and viciously beat them.

“In modern times, lathi is the primary weapon of the Indian riot

police along with helmets, shields, tear gas and other methods. Policemen are

trained in highly co-ordinated drill movements which can leave many of the rioters

crippled. This drill has been quite controversial among human rights activists so

in many places the police do not follow the drill but hit in such a way to disperse

the crowds. Security guards and police officers often carry a lathi along with or

in place of firearms. They prefer lathi for their ease of use and comparative

safety and only resort to firearms in situations when lathi cannot be used

efficiently.” —Wikipedia article on lathis.

LAZARUS, Sylvain (1943- )

A radical bourgeois French sociologist, anthropologist and political theorist, and longtime

political and philosophical associate of the “post-Maoist”

Continental philosopher

Alain Badiou. In his youth he was strongly influenced by

the May 1968 uprisings in France and by the Great Proletarian Cultural

Revolution in China. In late 1969 he (along with Badiou and others) founded the Union

des communists de France marxiste-léniniste (UCFML) which was a nominally

“Maoist” organization. (I.e., the intellectuals in this small sectarian group were

enthusiastic about Mao and the GPCR, insofar as they actually knew much about them.)

In 1981, using the nom de plume Paul

Sandevince, Lazarus published a piece entitled “Notes de travail sur le post-léninisme”

[“Working Notes on Post-Leninism”] in which he openly talked about his deep dissatisfaction

with many essential principles of Marxism-Leninism, and called for a new type of “post-Leninist”

political party. In 1985, after the collapse of the UCFML, Lazarus, Badiou and some of the

others formed a new group they called L’Organisation Politique, which did not consider

itself to be a revolutionary political party nor to be working toward the creation of one.

Its only mass practice was around a few reformist issues (especially promoting the rights of

immigrants in France). The OP itself fizzled out, and apparently completely disappeared by

2007 at the latest.

By the year 2001 Lazarus and Badiou were openly

rejecting the need for any proletarian class perspective whatsoever in politics, as well as

the need for any revolutionary party of any sort. (See the BADIOU entry

for quotes about this.) No doubt Lazarus and his friends once had some youthful revolutionary

spirit, but that has long since disappeared. Indeed, it seems quite unlikely that they were

ever really genuine Maoist revolutionaries in the first place.

LEAGUE OF RUSSIAN REVOLUTIONARY SOCIAL-DEMOCRACY ABROAD

“The League of Russian Revolutionary Social-Democracy Abroad

was founded in October 1901 on Lenin’s initiative, incorporating the Iskra-Zarya

organization abroad and the Sotsial-Demokrat organization (which included the

Emancipation of Labor group). The

objects of the League were to propagate the dieas of revolutionary Social-Democracy

and help to build a militant Social-Democratic organization. Actually, the League was

the foreign representative of the Iskra organization. It recruited supporters

for Iskra among Social-Democrats living abroad, gave the paper material support,

organized its delivery to Russia, and punblished popular Marxist literature. The

Second Party Congress endorsed the League as the sole Party organization abroad, with

the status of a Party committee and the obligation of working under the Central

Committee’s direction and control.

“After the Second Party Congress,

the Mensheviks entrenched themselves in the League and used it in their fight against

Lenin and the Bolsheviks. At the Second Congress of the League, in October 1903, they

adopted new League Rules that ran counter to the Party Rules adopted at the Party

Congress. From that time on the League was a bulwark of Menshevism. It continued in

existence until 1905.” —Note 15, LCW 7.

LEAGUE OF STRUGGLE FOR THE EMANCIPATION OF THE WORKING CLASS

“The League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working

Class was organized by Lenin in the autumn of 1895; it embraced about twenty

Marxist workers’ study circles in St. Petersburg. The work of the League of Struggle

was organized in its entirety on principles of centralism and strict discipline. The

League was headed by a Central Group consisting of V. I. Lenin, A. A. Vaneyev, P. K.

Zaporozhets, G. M. Krzhizhanovsky, N. K. Krupskaya,

L. Martov (Y. O. Tsederbaum), M. A. Zilvin, V. V. Starkov

and others. Direct leadership was in the hands of a group of five headed by Lenin.

The organization was divided into district groups. Advanced, class-conscious workers

(I. V. Babushkin, V. A. Shelgunov and others) linked these groups with the factories.

At the factories there were organizers who gathered information and distributed

literature; workers’ study circles were set up at the biggest establishments.

“The League of Struggle was the

first organization in Russia to combine socialism with the working-class movement.

The League guided the working-class movement, linking up the economic struggle of the

workers with the struggle against tsarism, it published leaflets and pamphlets for

the workers. Lenin was the editor of the League’s publications and preparations for

the issue of a working-class newspaper, Rabocheye Dyelo, were made under his

leadership. The influence of the League of Struggle spread far beyond St. Petersburg.

Following its example, workers’ study circles were united into Leagues of Struggle

in Moscow, Kiev, Ekaterinoslav and other towns and regions of Russia.

“In December 1895, the tsarist

government dealt the League a heavy blow. During the night of December 8-9 (December

20-21 New Style) a considerable number of League members were arrested, Lenin among

them; the first issue of Rabocheye Dyelo that was ready for the press was

seized.

“At the first meeting held

after the arrests it was decided to call the organization of St. Petersburg

Social-Democrats the League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working

Class. As an answer to the arrest of Lenin and the other members of the League,

those who escaped arrest issued a leaflet on a political theme; it was written by

workers.

“While Lenin was in prison he

continued to guide the work of the League, to help with advice; he sent letters and

leaflets written in cipher out of prison and wrote the pamphlet ‘Strikes’ (this

manuscript has not been discovered), and ‘Draft and Explanation of a Programme for

the Social-Democratic Party’ (LCW 2:93-121).

“The St. Petersburg League of

Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class was important, to use Lenin’s

definition, because it was the germ of a revolutionary party that took its support

from the working class and led the class struggle of the proletariat. In the latter

half of 1898 the League fell into the hands of the Economists

who planted the ideas of trade-unionism and Bernsteinism

on Russian soil through their newspaper Rabochaya Mysl. In 1898, however, the

old members of the League who had escaped arrest took part in preparing the way for the

First Congress of the R.S.D.L.P. and in drawing up the Manifesto of that Congress, thus

continuing the traditions of Lenin’s League of Struggle.” —Note 119, Lenin SW1

(1967).

LEFT vs. “LEFT”

Since the days of the great French Revolution

the left has referred to those in politics who want progressive change in the

interests of the people, rather than maintaining the status quo or even change backward

in a reactionary direction. However, within the revolutionary Marxist milieu, the

left refers to genuine revolutionaries and not mere reformers. For Marxists,

the “left” or “leftist”, when it is in scare-quotes like that, refers not to the genuine

left, but rather to the phony, so-called “left” which is actually opposed to revolution,

or else to “ultra-leftists” whose inappropriate slogans and actions will not actually

lead the situation forward to revolution.

Thus what a particular individual means

by the left or leftist depends on their own political views (and specifically

whether they are a true and rational revolutionary or not).

“Guard against ‘Left’ and Right deviations. Some people say, ‘It is

better to be on the “Left” than on the Right,’ a remark repeated by many comrades. In

fact, there are many who say to themselves that ‘It is better to be on the Right than

on the “Left”’, but they don’t say it aloud. Only those who are honest say so openly.

So there are these two opinions. What is ‘Left’? To move far ahead of the times, to

outpace current developments, to be rash in action and in matters of principle and

policy and to hit out indiscriminately in struggles and controversies—these are

‘Left’ deviations and are no good. To fall behind the times, to fail to keep pace

with current developments and to be lacking in militancy—these are Right deviations

and are no good either. In our Party there are people who prefer to be on the ‘Left’,

and then there are also quite a few who prefer to be on the Right or to take a

position right of center. Neither is good. We must wage a struggle on both fronts,

combating both ‘Left’ and Right deviations.” —Mao, “Speeches at the National

Conference of the Communist Party of China: Concluding Speech” (March 31, 1955),

SW 5:167.

“LEFT-WING” COMMUNISM

This term designates different groups of erring Communists (or communist-minded people),

often semi-anarchists, at different times and places.

1) The group within the Bolsheviks in 1918

who opposed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk signed in December 1917 which ended World War I

between Germany and Russia. This included Nikolai Bukharin,

Karl Radek and G. L. Pyatakov. Leon Trotsky also opposed

this Treaty, and is sometimes included within this group of “left-wing” communists, and is

sometimes mentioned separately from them. This whole group correctly recognized that the

Treaty was a bitter pill, but failed to understand that the survival of the Revolution

depended on accepting it. The Seventh Congress of the Party in March 1918 rejected the

position of this group.

2) The trend within the fledgling

international Communist movement after the success of the Bolshevik Revolution and the

end of World War I, especially in Germany and other European countries. This is the trend

Lenin strongly criticized in his pamphlet, “Left-Wing” Communism—An Infantile Disorder

(see entry below).

3) Similar semi-anarchist, ultra-“leftist”,

or propaganda-oriented trends and groups which are totally divorced from mass struggle, at

other times and places.

“LEISURE AGE”

Apologists for capitalism have periodically predicted that, “in the future”, capitalism

will be producing so much with so little effort by the workers, that there will be a

“golden age of leisure”. However, despite all the productivity improvements during the

capitalist era, and the immense productive capacity of capitalism (much of which is

not even used!), somehow this age of leisure never seems to dawn. The trend is actually

now for people to work longer and longer hours; that is, for those who have jobs at

all. The only life of comfortable leisure under capitalism is for those who own the means

of production; the “leisure” of the long-term or permanently unemployed is mostly a life

of misery.

“In the 1970s there was much talk of an imminent ‘leisure age’ in

which, thanks to automation, we would scarcely work at all—and a spate of books

brooding earnestly on how we would fill our new spare time without becoming

hopelessly lethargic. Anybody spotting one of these forgotten tracts in a second-hand

bookshop today would laugh incredulously. The average British employee now puts in

80,224 hours over his or her working life, as against 69,000 hours in 1981. Far from

losing the work ethic, we seem ever more enslaved by it. The new vogue is for books

that ask anxiously how we can achieve a ‘work-life balance’ in an age when many

people have no time for anything beyond labour and sleep.” —Francis Wheen,

Marx’s Das Kapital: A Biography (2006), p. 59.

LENIN — On the Agrarian Question

“In his writings on the agrarian question, Lenin provides, in the

first place, an analysis of the laws of development of capitalism in agriculture,

based on a wealth of statistical information from European countries and from the

U.S.A.

“This analysis is to be found

in his writings:

Capitalism in

Agriculture.

The Agrarian

Question and the ‘Critics’ of Marx.

New Data on

the Laws of Development of Capitalism in Agriculture.

The Agrarian

Programme of Social Democracy in the First Russian Revolution.

“These writings are difficult to

follow unless the reader has previous acquaintance with the main ideas of Marxist

economics. They are an important continuation and application of the principles of

Marx’s Capital. They constitute an indispensable part of Marxist studies

particularly for those concerned with agricultural questions. They are all polemical

in style, being directed against writers who either denied the capitalist development

of agriculture altogether or misrepresented its laws of development.

“In Capitalism in Agriculture,

Lenin deals with a Narodnik writer who had criticized Kautsky’s book on the agrarian

question (written at a time when Kautsky was still a Marxist). Lenin makes clear a

number of fundamental characteristics of the development of capitalism in agriculture—the

proportion of constant to variable capital increases in agriculture, as in industry;

there takes place a concentration of land-ownership in the hands of landlords and

mortgage corporations; large-scale production supplants small-scale, not merely by

increase in the area of farms but also by increase of intensity of production on a

small area; there is a growth of wage labor and of the utilization of machinery. He

then shows further how the development of capitalist agriculture is hampered by various

difficulties and contradictions, particularly ground rent, the growth of the urban at

the expense of rural population, and competition of cheap grain from newly developed

areas overseas where the producers are not burdened by ground rent.

“The same questions are again

taken up in The Agrarian Question and the ‘Critics’ of Marx. Here, after a

fundamental explanation of the fallacy of the so-called ‘law’ of diminishing returns,

and an exposition of the Marxist theory of ground rent, Lenin deals especially with

the question of large-scale versus small-scale farming, exposing the error of those

who imagine that small farming is more ‘progressive.’

“New Data on the Laws of

Development of Capitalism in Agriculture brings out further the points already

explained by means of a profound analysis of the development of agriculture in the

United States. Amongst other points emphasized both in this and the previous articles

is the essentially capitalist character of agricultural co-operation, in a capitalist

state, through farmers’ co-operative associations. [But see also Lenin On

Co-operation.]

“In The Agrarian Programme

of Social Democracy in the First Russian Revolution, 1905-7, Lenin gives a

detailed analysis of the existing system of land ownership in Russia and of the

tasks of the agrarian revolution in Russia.

“The key issues are confiscation

of the estates of the landlords and nationalization of the land. Lenin proves that

the nationalization of the land, in a capitalist state, does not destroy capitalism

in agriculture but, on the contrary, by removing the main obstacles to the free

investment of capital in agriculture, furthers its development. This point is

developed in Chapter III, which also contains a simply exposition of the Marxist

theory of ground rent....

“Two writings by Lenin dealing

with the agrarian question in pre-revolutionary Russia must be noted here, in

addition to the treatment of the development of capitalism in Russian agriculture

contained in the relevant chapters of [Lenin’s book] The Development of Capitalism

in Russia.

“In The Agrarian Question in

Russia at the End of the Nineteenth Century, Lenin gives a detailed analysis of

the types of farming in Russia and of their development, of the classes, of the

process of division of the peasants, and concludes that two alternative paths of

development were open to Russian agriculture—the ‘Russian’ path, through the growth

of kulak farming, or the ‘American’ path, through the nationalization of the land.

This analysis provided the basis for the agrarian programme of Russian

Social-Democracy, including its demand, voiced later, for the nationalization of

the land.

“In the booklet To the Rural

Poor published in 1903 for illegal distribution amongst the peasants, we find

a model of the simple, popular and forceful presentation of the party’s whole

economic and class analysis and programme of action.”

—Maurice Cornforth, Readers’

Guide to the Marxist Classics (1953), pp. 41-42.

LENIN — On Mass Democracy and the Mass Line

A fact not commonly recognized, even by many Maoists today, is that Lenin had a great

appreciation for the wisdom and abilities of the masses, for the importance of mass

democracy, for the central role of the masses in making revolution, and even a grasp

(perhaps mostly intuitively) of what became known in Maoist China as “the

mass line” method of revolutionary leadership.

[More to be added.]

“[O]n the one hand the character of the Soviets guarantees that

all these new reforms will be introduced only when an overwhelming majority of the

people has clearly and firmly realized the practical need for them; on the other

hand their character guarantees that the reforms will not be sponsored by the

police and officials, but will be carried out by way of voluntary participation of

the organized and armed masses of the proletariat and peasantry in the management

of their own affairs.” —Lenin, “Resolution on the Current Situation”, May 16 (3),

1917, LCW 24:311.

[These are quite similar to

the basic points that Mao made when he said that: “There are two principles here:

one is the actual needs of the masses rather than what we fancy they need, and the

other is the wishes of the masses, who must make up their own minds instead of our

making up their minds for them.” —Mao, Quotations, ch. XI; originally from

“The United Front in Cultural Work” (Oct. 30, 1944), SW 3:236-7.]

LENINISM

The further development and extension or modification of Marxism which is attributed

(either correctly or incorrectly) to V. I. Lenin. The term ‘Marxism-Leninism’ refers to

the science of revolutionary Marxism which includes the contributions of Lenin (as

well as those of Marx, Engels and others), while the term ‘Leninism’ itself tends to

focus more on those elements of Marxism-Leninism which are attributable (properly or

not) to Lenin specifically and not primarily to Marx and Engels. Thus those who

imagine that Marx was a bourgeois humanist and Lenin was not, will see a larger part of

Marxism-Leninism (as it is usually understood) as being due to Lenin, than those who

see more agreement between the ideas of Marx and Lenin in the first place. Therefore,

what is counted as distinctively ‘Leninist’ depends on the speaker’s notion of what

Marxism itself was properly viewed as before Lenin, as well as their notion of

how Lenin influenced and/or developed Marxism.

Leninism as it should be properly

understood by revolutionary Marxists includes at least these main overall points:

1) The application of Marxism to the

particular cirmstances and conditions of Russia;

2) The regeneration of Marxism as a

revolutionary theory after its degeneration into bourgeois reformism in

the Second International after the death of Marx and Engels;

3) The further development of

Marxism in the changed conditions of the new capitalist-imperialist era, and with the

successful October Revolution in Russia. And within this 3rd point, the

following main sub-points:

a) The recognition that

capitalist-imperialism was a whole new stage of capitalism, that it necessarily

involved both predatory wars and inter-imperialist wars, and that it represented a

further diseased and moribund social system which had become ripe for revolution,

including wars of national liberation in imperialist colonies.

b) A greater emphasis on the role of

the revolutionary proletarian party, along with a somewhat different conception of

the character of such a party (as a party of professional revolutionaries organized

on the basis of democratic centralism);

c) The actual direction of a

proletarian revolution and the implementation of the first major dictatorship of the

proletariat, and in the course of that developing many of the essential principles

of proletarian rule.

See also entries below.

“To expound Leninism means to expound the distinctive and new in

the works of Lenin that Lenin contributed to the general treasury of Marxism and

that is naturally connected with his name.” —Stalin, “The Foundations of Leninism”,

lectures delivered at the Sverdlov University, April-May 1924, Works 6:71.

“It is usual to point to the exceptionally militant and exceptionally

revolutionary character of Leninism. This is quite correct. But this specific feature

of Leninism is due to two causes: firstly, to the fact that Leninism emerged from

the proletarian revolution, the imprint of which it cannot but bear; secondly, to the

fact that it grew and became strong in clashes with the opportunism of the Second

International, the fight against which was and remains an essential preliminary

condition for a successful fight against capitalism. It must not be forgotten that

between Marx and Engels, on the one hand, and Lenin, on the other, there lies a whole

period of undivided domination of the opportunism of the Second International, and

the ruthless struggle against this opportunism could not but constitute one of the

most important tasks of Leninism.” —Stalin, ibid., Works 6:73-74.

LENINISM — Bourgeois Conception Of

Bourgeois writers often recognize, to some limited degree, some of the elements of

Leninism as we revolutionary Marxists understand it. (See entry above.) In particular

they often recognize the greatly increased attention Leninism gives to colonial or

semi-colonial countries, to the potential role for earlier revolutions that Leninists

see there, to the revolutionary potential of the peasantry, and so forth. They

sometimes even tie this loosely together with some partial recognition of imperialism

(though never as something inherent in modern capitalism!). But the one

thing that bourgeois writers most focus on in their discussion of what they

call “Leninism”, to the point where everything else is almost totally obscured, is

the nature and role of the Leninist party.

This conception of Leninism starts

with some actual elements of Lenin’s ideas about a revolutionary party, though it

tends to grossly distort or exaggerate them as follows:

1) The working class and masses are

presumed to be seldom, if ever, spontaneously revolutionary;

2) The working class is presumed to

be only capable of reformist or trade union consciousness on its own;

3) A revolutionary party is viewed

as absolutely essential in all circumstances to bring revolutionary ideas to the

workers and masses from the outside, and to lead them in a revolutionary

direction;

4) This party must be composed of

carefully and thoroughly trained, full-time professional revolutionaries;

5) The party must be tightly

organized and highly disciplined according to the principles of democratic

centralism—which the bourgeois ideologists assume must really be highly authoritarian

and totally undemocratic;

6) This party must be viewed as the

vanguard of the proletariat, even when it is first formed by a small number

of people, because only through its leadership can the masses make revolution;

7) This party, will institute what

it calls the “dictatorship of the proletariat” when it achieves power, but this will

actually be a dictatorship of the party (and ultimately of the top party leadership)

over the masses, and must inevitably operate in a “totalitarian”, fascist manner.

8) And finally, under this bourgeois

conception of Leninism, when the party actually is in power in one or more countries,

it will be bent on total world conquest.

Well! That is the bourgeois

conception of Leninism! This is obviously a total parody of Lenin’s ideas and of

genuine Leninism. Points 1 and 2 are already quite exaggerated; Lenin never claimed

that there were no spontaneous revolutionary ideas among the masses! He was well aware

of the great Paris Commune, for example, which was

created by a spontaneous uprising. Lenin only argued that the dominant forms of

spontaneity in bourgeois society are indeed reformist

in perspective, and that therefore the most class conscious section of the

masses, which constitutes itself into a proletarian party, must of course provide

leadership for the whole revolutionary movement.

Point 3 is distorted in at least two

major ways: First, there are times (such as during the Great

Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China) when the party has lost its way

and must itself be corrected and reconstituted by the revolutionary masses. Second, most

of the revolutionary ideas which the party brings to the masses do not really

come from “the outside”, but instead from among the masses themselves through the use

of Marxist summation and the method of the mass line.

Point 4 is basically true of genuine

Leninism; we do seek to build a party whose core, at least, is composed of

carefully trained professional revolutionaries. We also insist, however, that this

party have very close ties to the masses, that in socialist society (at least) party

members also spend substantial time participating in labor, and that the masses keep a

close eye upon the party and supervise it, so that it always remains working in

their interests! It is also true, as point 5 in the bourgeois conception of

Leninism has it, that a Leninist party should be highly organized and highly disciplined.

However, a true Leninist party actually takes the democracy aspect of democratic

centralism seriously and even insists that democracy must be the principal

aspect.

With regard to point 6: There has

indeed been a very wrong tendency in many new or small MLM parties, which are not yet

even in much contact with the masses in their country, to falsely view themselves as

a “vanguard”. A true vanguard is a party that is

actually out front and really leading the masses in struggle, and in

the direction of social revolution. This is very different than any self-proclaimed

miniscule phony “vanguard”.

In point 7 the bourgeois ideologues

of course conclude that any dictatorship over their class and their

supposed inalienable rights, must in fact be a vicious, totalitarian dictatorship

over the people as a whole. But what genuine Leninism (and Marxism!) means by the

dictatorship of the proletariat

is a society in which the working class and broad masses have full and complete

democratic rights, far more so than they have under

bourgeois democracy for example. No party

which exercises dictatorship over the people is a Leninist party, no matter

what it calls itself. Yes, revisionism in

power does this (as in Soviet Union from at least the mid-1950s on), but we actual

Leninists are deadly opponents of these revisionists.

And finally, with respect to point

8, we Leninists are indeed determined to bring about social revolution everywhere

in the world, and create world communism. Of course this is something very different

than “world conquest” in the sense the bourgeoisie understands it! Anyway, this is

actually nothing new in Leninism; Marx and Engels proclaimed this goal in the

Communist Manifesto long before Lenin was even born.

So the bourgeois conception of

“Leninism” is a complete distortion of the real thing. It is an almost complete lie

and slander of Lenin, which starts from small distortions and builds toward total

nonsense. It is true that Leninism does give more emphasis to the leading role of

the party than does Marx or Engels, and does have a somewhat different conception

of what such a party must be like. But, first, this is a natural development and

extension of the ideas of Marx and Engels, and second, this is only one aspect of

Leninism as it should be properly understood.

LÉVI-STRAUSS, Claude (1908-2009)

A prominent bourgeois anthropologist and sociologist, often considered in academic circles to

be the “father” of modern anthropology. He was influenced by linguistics, geology, Freudian

psychoanalysis and possibly to some limited extent by Marxism (as he himself claimed). He

introduced the concepts of “structuralism” from linguistics

and geology into anthropology and sociology, where it became an intellectual fad for a short

period.

One aspect of “structuralism” in anthropology,

as Lévi-Strauss understood it, was that all societies follow certain universal patterns

of thought and behavior. This is the sort of principle that obviously has some validity

to it, but which can easily be pushed to unreasonable extremes. A progressive aspect of this

way of looking at human culture is that it opposed the traditional attitudes towards native

peoples as being biologically “primitive” and having “savage” or “primitive” mental capabilities.

A less positive aspect of this way of looking at culture is that it tended to lead to the

“postmodern” idea that all worldviews

are “equally valid”, and that more modern forms of society are not really more advanced than

those of primitive societies. While it is true that the people in hunter-gatherer society,

for example, are not biologically primitive, their societies definitely are primitive,

and their traditional conceptions of the world are also definitely primitive as compared with a

modern scientific outlook.

Lévi-Strauss not only had a great

influence within anthropology and sociology, he also influenced the intellectual and academic

communities in general, especially in literary theory and Continental philosophy. Unfortunately,

this influence proved to be mostly negative.

LGBT

An acronym which refers to people who are lesbian, gay (homosexual), bisexual or transgender.

A recent (early 2013) Gallup poll of more than

200,000 Americans found that 3.5% of the population identifies as being within this group of

people.

In class society there has long been tremendous

oppression and mistreatment by the authorities and by the rest of the populace against LGBT

people, including even outright murder of them. In recent decades there have been some positive

changes in the attitudes of people in most advanced capitalist countries in this regard, but

LGBT people still suffer great inequality and mistreatment even in the more enlightened countries.

Of course, where there is oppression there is resistence, and the struggle for LGBT rights has

already become substantial in many countries.

Variations on this acronym include: LGBTQ

(which includes people who prefer to identify themselves as queer); LGBTQQ (which

further includes people who are questioning their own gender identity); and LGBTI

(which includes intersex individuals, i.e. those with a physical combination of both male

and female genitalia).

“LGBT is an initialism that collectively refers to the lesbian, gay, bisexual,

and transgender community. In use since the 1990s, the term LGBT is an adaptation of the

initialism LGB, which itself started replacing the phrase gay community beginning in the

mid-to-late 1980s, which many within the community in question felt did not accurately represent

all those to whom it referred. The initialism has become mainstream as a self-designation and

has been adopted by the majority of sexuality and gender identity-based community centers and

media in the United States and some other English-speaking countries.

“The term LGBT is intended to emphasize a

diversity of sexuality and gender identity-based cultures and is sometimes used to refer to

anyone who is non-heterosexual or non-cisgender instead of exclusively to people who are lesbian,

gay, bisexual, or transgender. To recognize this inclusion, a popular variant adds the letter Q

for those who identify as queer and/or are questioning their sexual identity as LGBTQ, recorded

since 1996.” —Wikipedia entry for ‘LGBT’ (accessed March 17, 2013).

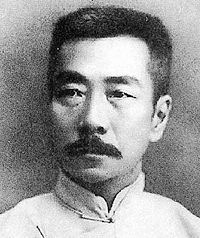

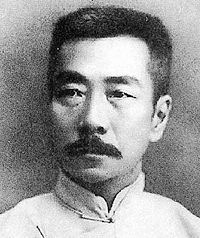

LI Da (1890-1966)

One of the earliest and most important Marxist philosophers and disseminators of Marxist

theory more generally in China. He was a founding member of the Communist Party of China and

played an important role in the Marxist education of Party members, including Mao Zedong.

From their already existing Japanese translations, Li Da retranslated many Russian and German

works on philosophy and Marxist theory into Chinese. Li’s own most important work was his

Elements of Sociology (1st ed., 1935), which is said to have had a great influence

on Mao. In the young Soviet Union there were some major struggles in philosophy, and by the

1930s a standard “New Philosophy” became dominant there. Li Da helped popularize that

standardized version of Marxist philosophy and theory in China.

During the Great

Proletarian Cultural Revolution Li Da was heavily criticized for having failed to

proclaim the absolute and total originality of Mao’s contributions to Marxist philosophy

and theory. However, Mao—like everyone else—had to learn a lot of his theoretical views from

his predecessors. Mao did make great contributions to Marxism, but he was able to do so in

part because of the earlier great ideas he learned from Marx, Engels, Lenin and others.

An important book about Li Da is: Li Da

and Marxist Philosophy in China (1996), by Nick Knight.

In March 1966, Li Da responded to Lin Biao’s theory that Mao Zedong

Thought was the pinnacle of Marxist-Leninist theory in characteristically forthright

manner. On being informed—possibly rather nervously—by one of his research assistants

that this theory originated from Vice Chairman Lin, Li responded:

“I realize that, and I don’t

agree! This notion of a ‘pinnacle’ is unscientific, and does not conform to dialectics.

Marxism-Leninism is developmental, and so is Mao Zedong Thought. If you compare them

to a pinnacle, then there is no direction in which they can develop from there. How

can Marxism-Leninism have a ‘pinnacle’? I can’t agree with violations of dialectics,

regardless of who utters it.”

—From Nick Knight, Li Da and

Marxist Philosophy in China (1996), p. 23. [While strictly speaking Li Da was

correct here, he might better have recognized that revolutionary theory can very well

reach temporary “pinnacles” as of a given time, which later can and should be

surpassed. Revolutionary theory, too, advances by periodic leaps which must be

recognized and defended. —S.H.]

LI Tso-p’eng (1916-?)

A General and high ranking political cadre in the People’s Liberation Army of China, who is known

both as the author of an influential article summing up one aspect of Mao’s military concepts

“Strategy: One Against Ten, Tactics: Ten Against One” (1964), and also later for his conspiratorial

involvement in the failed coup attempt by Lin Biao.

The Strategy and Tactics article appeared in an

abridged English translation in Peking Review,

1965, issues #15 & #16, and was also issued as a 43-page pamphlet in English in 1966. Excerpts

from it were published in the RIM magazine, A World to Win, #16 in 1991, online at:

http://www.bannedthought.net/International/RIM/AWTW/1991-16/strategy_One_Against_Ten_Tactics.htm

(The AWTW editors seemed not to be aware of Li’s role in the conspiracy to overthrow

and even murder Mao!)

From 1967 until his downfall immediately following

the attempted military coup by Lin Biao, General Li Tso-p’eng was the 1st political commissar of the

Navy. He had authority over the naval air base at Shanhaikuan and aided Lin and his family and

closest circle in their escape by air from that base. (However, the plane crashed in Mongolia, and

all aboard it were killed.) Li himself was soon arrested and then brought to trial for his

substantial role in the conspiracy.

“Seeing that his scheme had been exposed and that his last day was coming, Lin

Piao hurriedly took his wife and son and a few diehard cohorts to escape to the enemy, betraying

the Party and the state. In the early morning of 2:30, September 13, 1971, the Trident jet No.

256 carrying them crashed in the vicinity of Ondor Han in Mongolia. Lin Piao, Yeh Chun, Lin

Li-kuo [Lin Biao’s son], and all other renegades and aboard were burned to death. Their death,

however, could not expiate all their crimes. After Lin Piao’s unsuccessful betrayal and defection,

Huang Yung-sheng, Wu Fa-hsien, Li Tso-p’eng, and Ch’iu Hui-tso destroyed many evidences

to cover up their own criminal acts.” —“Document No. 24 of the CCP Central Committee,” a Party

document about the whole Lin Biao conspiracy, June 1972. [Emphasis added.]

LIBERALISM [U.S. bourgeois political sense]

[To be added...]

“Though it is difficult to recall, there was a time when liberalism

was identified with cheerfulness.... At the high-water mark of its recent political

influence, liberalism is depressed, disappointed, deflated.” —Michael Gerson, a

bourgeois commentator, in the Washington Post; quoted in The Week, Oct.

8, 2010, p. 16. [Although Gerson himself is a conservative, even most political liberals

themselves today show little confidence in their own perspective, and very little

enthusiasm or hope that a significantly better world will come about through the

implimentation of the policies of their elected leaders. They are suffering a crisis of

faith because of the long-term failure of their own program, and the obvious fact that

it has arrived at a dead end. —S.H.]

LIBERATION THEOLOGY

A movement that developed primarily in Roman Catholic countries during the world political

radicalizations of the 1960s, and is sometimes considered to be a form of Christian socialism.

It seeks to reinterpret Christian doctrine and activities from the perspective of the poor,

downtrodden and oppressed, and thus has a pro lower class political character as well as a

religious character. Theologians of this school view poverty itself as the result of sin,

the sin of exploitation by the capitalists and the sin of the class war that the rich wage

against the poor. Liberation theology was especially popular for a time in Latin American

countries which had formerly been colonies, and which it viewed as still suffering from

“post-colonial deprivation”.

One of the founders of liberation theology

was the Peruvian Dominican theologian, Gustavo Gutiérrez Merina (1928- ), who sought

to blend Marxism with Catholic social thought. His book, A Theology of Liberation:

History, Politics, Salvation (1971), was very influential among liberal Latin American

Catholics. Another influential work in this sphere was Liberation Theology, by the

Brazilians Leonardo and Clodovis Boff.

While basically just a Catholic reformist

movement there were a few cases of guerrilla warfare engaged in by renegade Catholic priests

and their associates. From the 1970s on liberation theology spread to some African countries,

where it focused on condemning apartheid and other forms of racism. Liberation theology also

inspired similar reformist trends such as Black theology, gay theology, etc. While liberation

theology still exists, especially in Brazil, it seems to have lost much of its original

radical force. In part this is due to the ferocious crackdown on this trend by

ultra-reactionary popes and the Catholic hierarchy.

“When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask

why the poor have no food, they call me a communist.” —Dom Hélder Câmara,

a Brazilian Archbishop.

LIFE — Origin Of

Specific details surrounding the origin of life are appropriate to the sciences of chemistry

and biology, and not revolutionary science. But, as materialists we view the origin of

life as having been of necessity a natural process, based originally on natural chemical

and physical processes.

“With regard to the origin of life, therefore, up to the present,

natural science is only able to say with certainty that it must have been the result

of chemical action.” —Engels, Anti-Dühring (1878), MECW 25:68.

“If life and death cannot be transformed into each other, then please

tell me where living things come from. Originally there was only non-living matter on

earth, and living things did not come into existence until later, when they were

transformed from non-living matter, that is, dead matter.” —Mao, “Talks at a Conference

of Secretaries of Provincial, Municipal and Autonomous Region Party Committees” (Talk of

January 27, 1957), SW 5:368.

LIN Biao [Old style: LIN Piao] (1908-71)

High-ranking military and political leader in revolutionary China who proved to be the

worst sort of careerist, and who betrayed the revolution and even attempted to assassinate

Mao.

Lin was born in Wuhan, in Hubei province,

and was the son of a factory owner. He was educated at the Wampoa Military Academy where

he became radicalized. When he graduated in 1926 he joined up with the Communist Party to

fight the Guomindang. He became commander of the Northeast People’s Liberation Army in

1945. In 1959 he was appointed Minister of Defense, and—apparently just for careerist

motives—made a very strong show of supporting Mao and opposing the capitalist-roaders

during the early years of the Great Proletarian Cultural

Revolution. This led to his appointment as the Vice-Chairman of the Party at the 9th

Party Congress in 1969, and Mao’s designated heir. But by 1971, Lin’s health was

deteriorating, and there were hints that he might be removed as Mao’s designated successor.

Fearing his personal grandiose career hopes were flitting away, and along with his son and

a few close supporters, he drew up a plan with the code name “Project 571” to assassinate

Mao during a train journey from Shanghai to Beijing, and then seize power in a military

coup. This plot was uncovered, and in September 1971 Lin tried to escape by air to the

revisionist Soviet Union. However, his plane crashed in Mongolia and he was killed.

In the years after his death a massive

political campaign to criticize Lin Biao together with Confucius took place in China.

There are indeed many lessons to be learned about how, especially after the seizure of

political power, the revolutionary proletariat must be alert for careerists and

unprincipled opportunists. Not only must communists be trained to be “honest and above

board” in putting forward their own views, but revolutionary parties must carefully avoid

awarding and promoting those who are mere opportunist toadies. “Yes men” are far more

dangerous to the revolution than those who at times honestly and openly disagree with the

party leadership. In reality, we should be highly suspicious of those who never

disagree with us! Either such people are just not thinking on their own, or else they

have ulterior motives for always agreeing with us. Either way, they should never be

promoted to high office in a revolutionary party or government.

See also:

ANTI-LIN BIAO, ANTI-CONFUCIUS

CAMPAIGN

LIQUIDATIONISM

1. The dissolution, termination or purposeful destruction of a revolutionary party

by those who are no longer revolutionaries, or the advocacy of such action. This has

sometimes been advocated by revisionists within socialist or communist parties on the

supposed grounds that social revolution is no longer necessary, and therefore that

revolutionary parties to lead such a revolution are no longer necessary. Obviously this

is an extreme form of right opportunism and betrayal of

the revolutionary goal.

2. The termination of the revolutionary struggle by those who have become revisionists

(whether or not this also involves formally dissolving the revolutionary party that had

been leading such a struggle). In many cases the revolutionary party is not actually

dissolved, but instead it is transformed into a reformist or other type of bourgeois

party.

“Liquidationism—an opportunist trend that spread among the

Menshevik Social-Democrats after the defeat of the 1905-07 Revolution [in Russia].

“The liquidators demanded the

dissolution of the illegal party of the working class. Summoning the workers to give

up the struggle against tsarism, they intended calling a non-Party ‘labor congress’

to establish an opportunist ‘broad’ labor party which, abandoning revolutionary slogans,

would engage only in the legal activity permitted by the tsarist government. Lenin and

other Bolsheviks ceaselessly exposed this betrayal of the revolution by the liquidators.

The policy of the liquidators was not supported by the workers. The Prague Conference

of the R.S.D.L.P. which took place in January 1912 expelled them from the Party.”

—Note 7, LCW 17.

LIU Shaoqi [Oldstyle: LIU Shao-ch’i] (1898-1969)

High ranking member of the Chinese Communist Party who during the period of socialism was

the leader of those in the Party taking the capitalist road toward the restoration of

capitalism in China. He was overthrown by the Maoist revolutionaries during the

Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

Liu was born in Hunan Province to a

moderately rich, land-owning peasant family. He was educated in Changsha and Shanghai

(where he learned Russian). In 1921-22 he went to study in Moscow, and while there joined

the newly-formed CCP. He returned to China and became a labor organizer in Shanghai. His

orientation was always more toward the cities than the countryside. He was elected to the

CCP Politburo in 1934 and became its expert on matters of organization and Party structure.

In 1939 he wrote his notorious book on “self-cultivation”, How to Be a Good Communist.

In 1943 he became Secretary General of the Party, then Vice-Chairman in 1949. While Mao was

still Chairman of the CCP, Liu became Chairman of the People’s Republic of China in 1958

(i.e., head of state).

Liu advocated and did his best to institute

all sorts of “reforms” tending in the direction of restoring capitalism, such as promoting

production above political consciousness; financial incentives and bonuses (as opposed to

moral incentives); easing of the restrictions on the market economy (rather than tightening

them and steadily restricting the “law of value”); promoting

rewards for “loyal cadres” and special treatment for the children of high Party officials;

and, in general, promotion of a new privileged strata within the Party and State. As the

Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution developed in the late 1960s Liu led the sly and

semi-camouflaged resistence to it. This had the effect of more and more turning the GPCR

against him and his minions as its primary target. In 1967 Liu was informally removed

from power, and in October 1968 he was formally “expelled from the Party forever, and